Looking Into The History

Public Archaeology Corps | Wilmington, NC

David Norris, Public Archaeology Corps Historian has been looking into the history of our dig site and the neighborhood. Wilmington’s surviving historic newspapers: New Hanover Deed Records and Probate and Will Books; Old maps; and other historical documents. These help provide context for the artifacts we are finding.

James Jennet’s 1790s Tavern

Quite a few of the artifacts found in our dig with the Public Archaeology Corps on Quince’s Alley — bowls and stems of clay tobacco pipes; shards of possible wine or liquor bottles; and fragments of plates, bowls, cups, and glasses – are the sort of artifacts excavated from tavern sites. And, indeed, surviving records of Wilmington and New Hanover County indicate that as many as five (or more) taverns, ordinaries, or bars may have operated near our dig site between the 1750s and the 1840s.

Technically, an ordinary was a combination bar-restaurant-hotel, with stabling for the horses of overnight guests, while a tavern was a bar that might also serve food. In practice, people often used both terms interchangeably. Ordinaries and taverns in colonial and later New Hanover County required annual licenses from the county court.

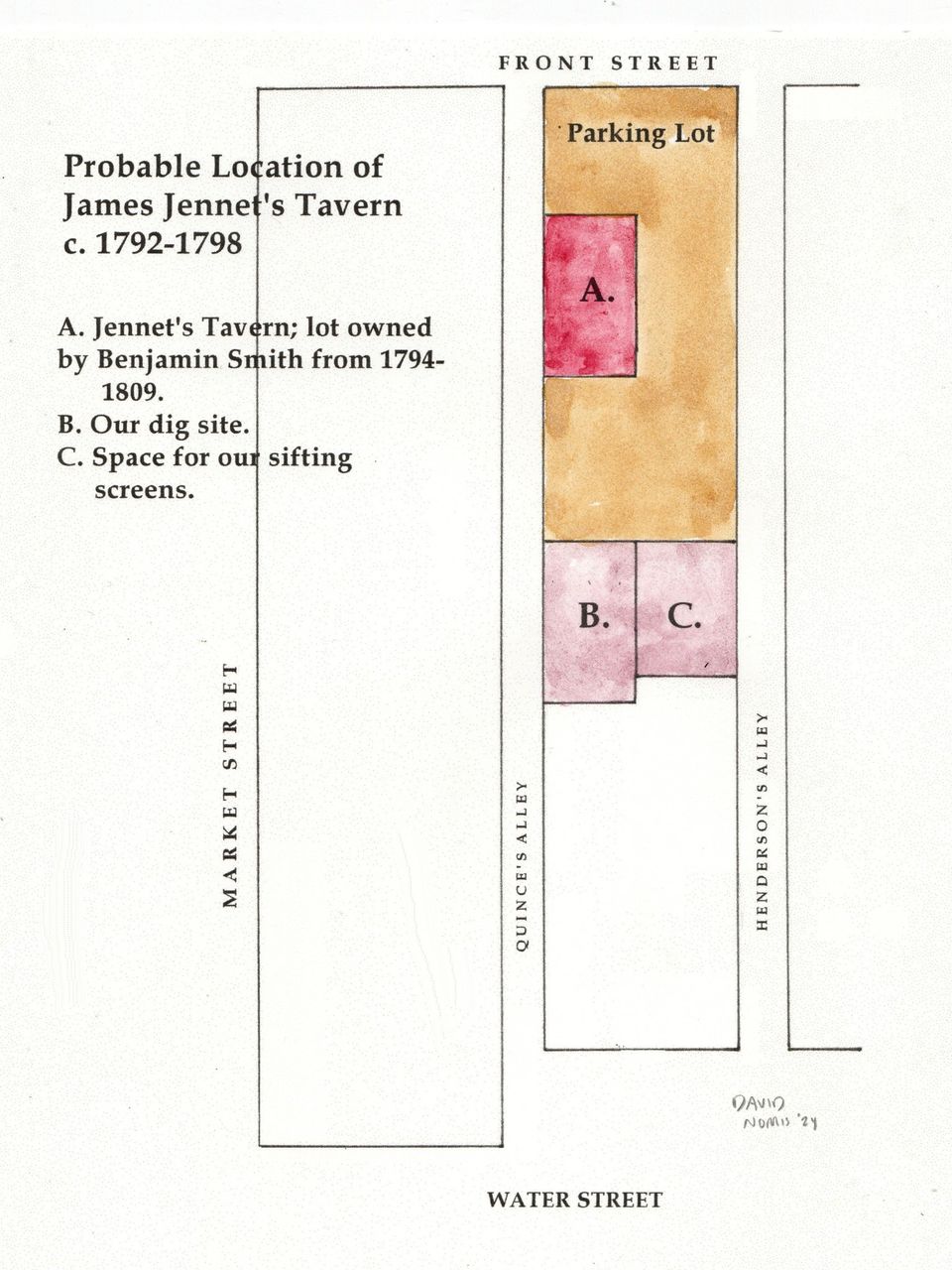

One of the taverns near our dig site was run by James Jennet. The New Hanover County Court first granted him a license to keep an ordinary in Wilmington in 1792. Surviving county court records show that he renewed his license at least twice, in 1793 and 1796.

A February 22, 1798 ad in Hall’s Wilmington Gazettenoted that there was a town house for sale “in Quince’s alley, which has long been occupied by James Jennet, and in use as a well frequented Tavern, the same having been lately repaired.” Unfortunately, Jennet’s Tavern was destroyed with practically the whole block in a fire on April 21, 1798. Jennet never renewed his tavern license after the fire.

In 1768, John Quince bought the lots along both sides of Quince’s Alley, from Front Street to the river. Soon after, he sold several parcels, including a lot running 42 feet along the south side of Quince’s Alley. The approximate position of the lot in the 1769 map of Wilmington by Joseph-Claude Sauthier shows a building, tinted in red watercolor on the map. The red tint is believed to represent brick buildings on the map.

At some point soon after 1768, William Evans obtained this 42-foot lot from Quince. Evans sold it to Peter Brown in 1778. A suspected Loyalist during the Revolutionary War, Brown suffered the confiscation of property by the patriot government. This lot changed hands a few times before Benjamin Smith bought it in 1794. Apparently, Smith rented the property to Jennet for use as a tavern. It was not uncommon for a house to be converted into a tavern, and the tavern keepers often lived in the same building.

The newspaper ad listing the tavern building for sale was among several placed by Benjamin Smith. Later serving as governor of North Carolina in 1810-1811, Smith owned Belvedere Plantation in Brunswick County, among numerous other lands. But, he only owned one lot on Quince’s Alley. Written records provide enough clues for us to know where this tavern stood.

The old Jennet’s Tavern place was evidently not rebuilt by April 15, 1806, when Smith offered his lot on Quince’s Alley for sale in the Wilmington Gazette. It took him until 1809 to sell it, when it was purchased by Col. Thomas Cowan. Later deeds for surrounding lots indicate that a lot on the northeast corner of Quince’s Alley and Front Street ran 28 feet west along the south side of the alley, where it joined the edge of the “42-foot lot”.

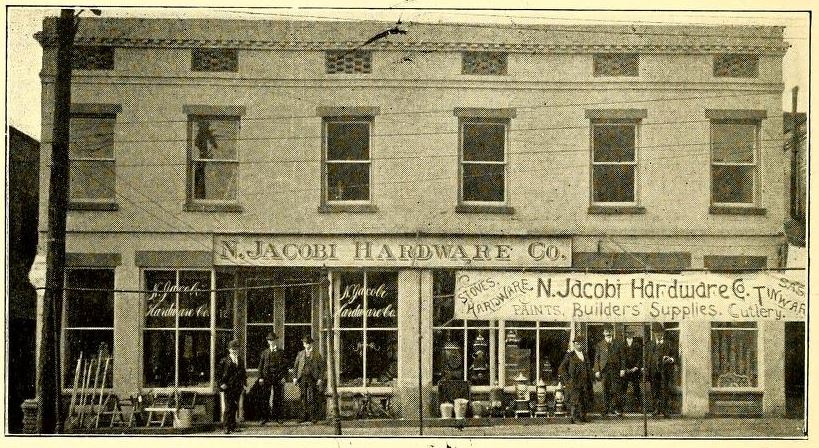

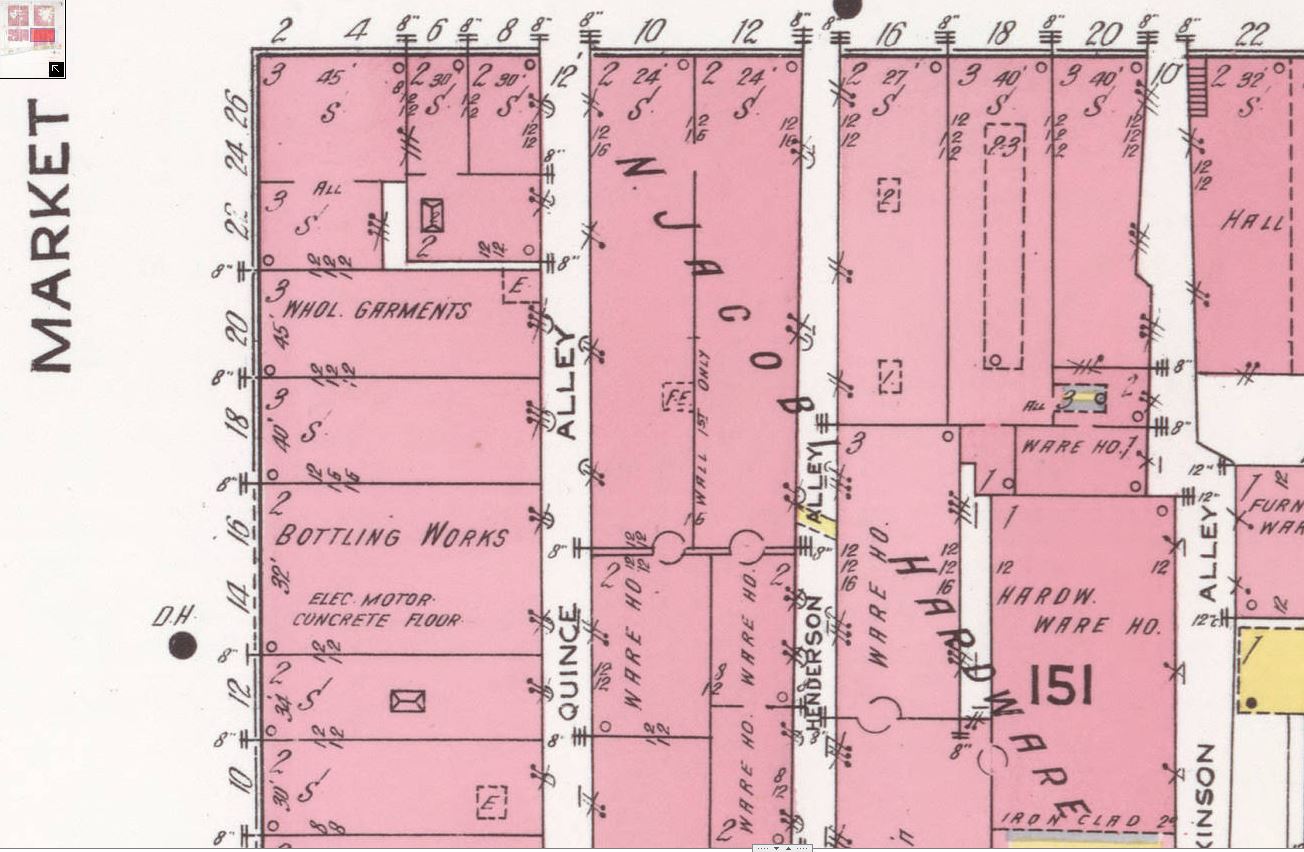

After Thomas Cowan died, the “42-foot lot” had several owners before another fire swept the block in 1845. New buildings appeared on the property. After the Civil War, a grocery store and a saddle and harness shop stood nearby on Front Street. The Jacobi Hardware Company moved there in 1870, and by 1901, that company owned the property between Quince’s and Henderson’s Alleys, running 117 feet back from Front Street to the walls of the brick buildings where Public Archaeology Corps is now working. Their hardware store and warehouse space filled the lot, covering up the former site of Jennet’s Tavern. Before World War II, the Jacobi Hardware Company moved out of 10-12 South Front Street, and the space was occupied by a men’s clothing shop and a jewelry store. After a fire in 1984, the damaged buildings were demolished and the site became the parking lot we see today.

1. The approximate site of Jennet’s Tavern, c. 1792-1798.

2. Benjamin Smith, owner of the Jennet’s Tavern lot from 1794-1809.

3. 10-12 Front Street about 1902.

4. The dig site and parking lot area, 1915 Sanborn Insurance Map.

Benjamin Smith, owner of the Jennet’s Tavern lot from 1794-1809

10-12 Front Street about 1902.

The dig site and parking lot area, 1915 Sanborn Insurance Map

Bathing Houses in Old Wilmington

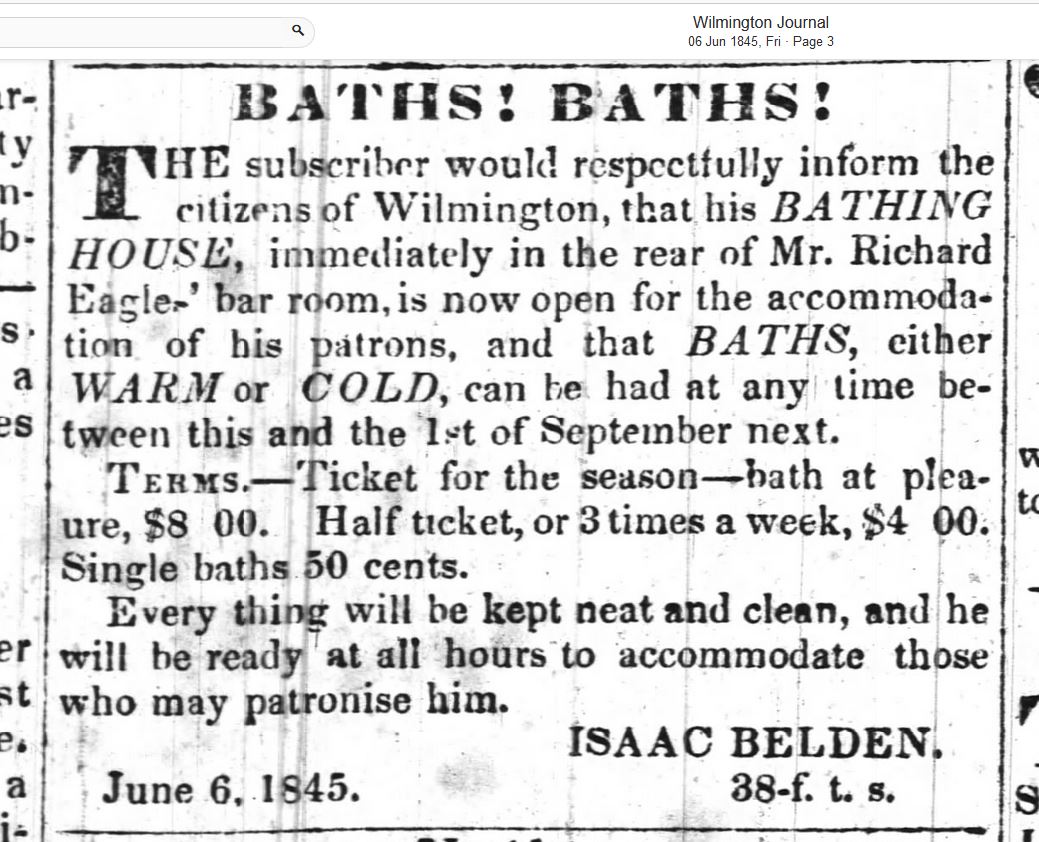

In 1842, an emancipated former slave turned businessman named Isaac Belden opened an oyster house on Quince’s Alley, where the Public Archaeology Corps has conducted a dig since 2019. As summer 1843 approached, with the cool-weather oyster season at an end, Belden advertised a new enterprise, a bathing house.

The Clarendon Water Works (Wilmington’s first water plant) didn’t provide citywide running water until 1881. It was possible (although expensive) to bring running water into an antebellum house, from a water tank, fed by water pumped from a well or cistern. But, for most households, hauling water inside and heating it up to pour into a bathtub took a great deal of time and effort.

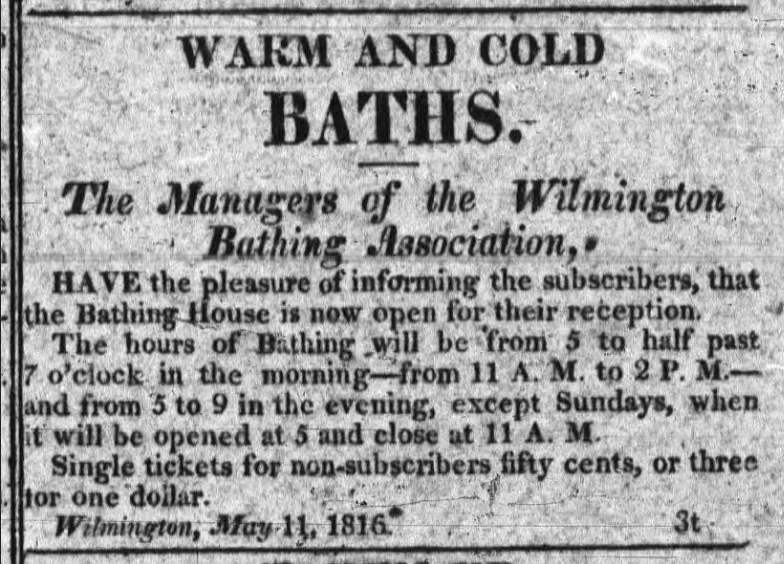

Belden’s was not the first public bathing house business in town. The Wilmington Bathing Association opened a bathing house on Front Street in May 1816. They were open daily from 5 a.m. to 7:30 a.m.; 11 am to 2 pm; and 5 to 9 pm; except Sundays, when they were open from 5 a.m. to 11 a.m. Non-subscribers could get a bath for 50 cents, or bathe three times for one dollar.

In the 1840s Belden also charged 50 cents for one bath. He offered a “ticket for the season” for $8, with as many baths as one wanted, or a $4 “half ticket”, which allowed three baths a week during the season.

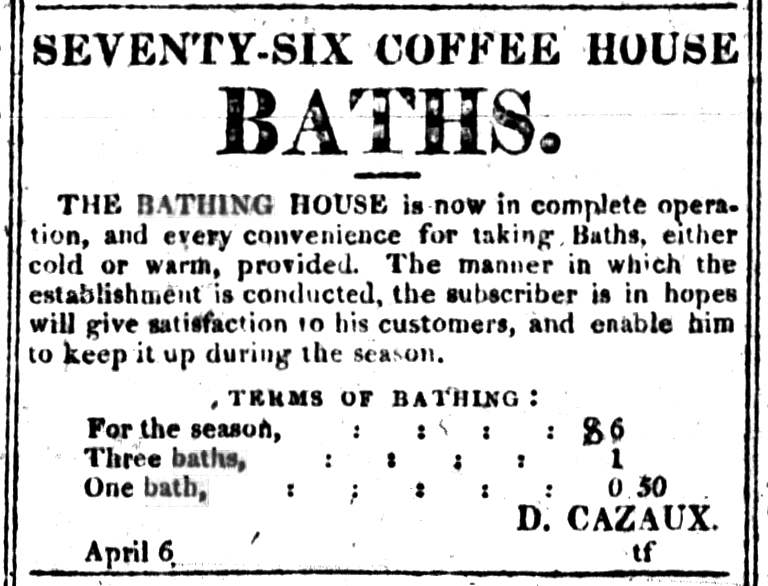

The “Old ‘76” tavern and hotel building stood on the east side of Front Street between Orange and Ann Streets. In 1819, owner Dominique Cazaux added bathing rooms to the business, which already included a coffee house, bar room, reading room (with a library of out-of-town newspapers), hotel rooms, and a stable. The Verandah Saloon, on the southeast corner of Water Street and Wilkinson’s Alley, added a bath house staffed with attendants in 1849.

By 1856, the “eating saloon” at the city’s Wilmington & Weldon Railroad Depot had “a number of bathing rooms, elegantly fitted up for warm or hot baths”, according to the Wilmington Journal.

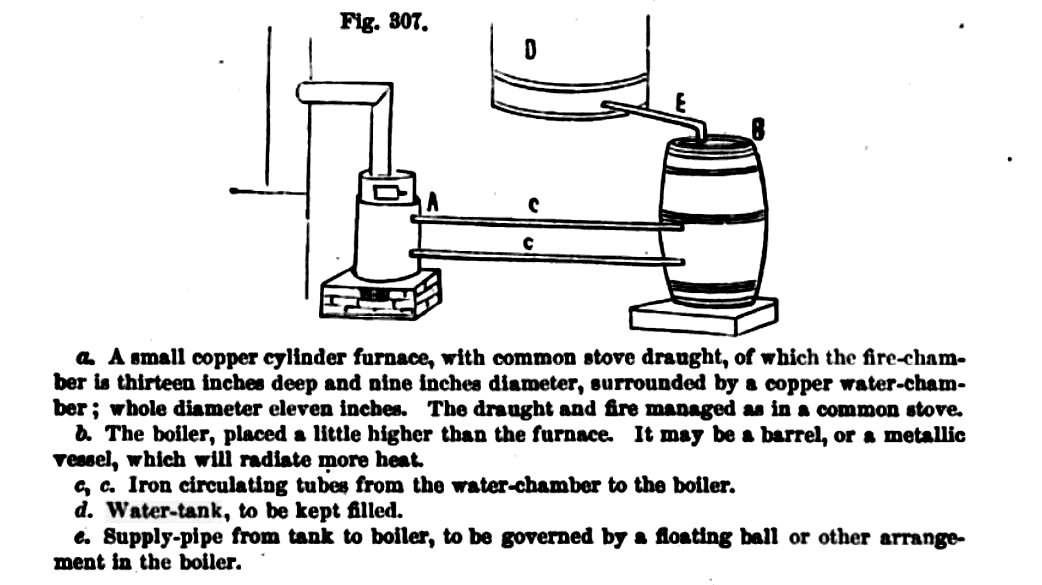

Little detail was given in the Wilmington papers about the set-up of the 1800s bathing houses. One might expect water tanks; tubs; pumps; drains; and some sort of furnace or heating source for the water. In Savannah, Georgia, an 1850 fire was thought to have started in a bathing house “with stoves and other apparatus for heating water”, according to the Wilmington Journal.

In 1870, the contents of a shaving saloon at Front and Princess were offered for sale. Among the items were “4 Bath Tubs, Faucets and Fixtures, 3 Marble Slabs, 1 Centre Table, 1 Square Table, Towels, Aprons, &c.”

Wilmington’s most elaborate bathing establishment was certainly J. W. Spaulding’s Floating Bath House. Opened in 1870, the bath house was built on a flatboat anchored near the ferry dock at the foot of Market Street. Two 10 x 30-foot wings, enclosed on the sides and bottom by lattice work, held bathers safely in a sort of pool about 3 to 5 feet deep. Changing rooms were built on the flatboat, and a large roof covered the whole thing.

The Floating Bath House was more for swimming than bathing for cleanliness. The downtown riverbank itself attracted bathers during the 1800s. Whether trying to keep clean or cool off on hot summer days, quite a few 19th century skinny-dippers were arrested at Greenfield Pond, or along the river downtown between Harnett and Castle Streets. Another problem was that people took baths in the Rock Spring at the foot of Chestnut Street – which was a source of drinking water for people living in that part of town!

Illustrations: 1. One of Isaac Belden’s ads for the bathing house on Quince’s Alley (Wilmington Journal, June 6, 1845). 2. Ad for the Wilmington Bathing Association (Cape-Fear Recorder, May 20, 1816). 3. Ad for the Seventy-Six Coffee House (Cape-Fear Recorder, April 13, 1825). 4. A system for heating water at home; perhaps Isaac Belden had something like this installed at his bathing house on Quince’s Alley. (Alexander Watson, American Home Garden. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1859.)