History of Our Finds

Public Archaeology Corps | Wilmington, NC

David Norris, Public Archaeology Corps Historian has been looking into the history of our dig site and the neighborhood. Wilmington’s surviving historic newspapers: New Hanover Deed Records and Probate and Will Books; Old maps; and other historical documents. These help provide context for the artifacts we are finding.

Quick Links To Our Finds and Stories

- A Look at Our Mysterious Millstone

- James Jennet’s 1790’s Tavern

- Bathing Houses

- Pipes

- Bone Buttons and Button Blanks

- Toothbrush

- Bottles

- Wig Era

- Window Glass

- Cumberford Lot

- Two Fires

- Oysters of Quince Alley

- Bar Shot of Quince’s Alley

- Hilton Plantation (video)

- Mocha Ware in Quince Alley

- Musical Fragment of Transferware

- Chamber Pot

- Blue Mineral Water Bottle

- King George’s Tobacco Pipe Bowl

- Brushes with Bone Handles

- Black Transferware Map Fragments

- A Look at our Black Transferware Fragments that Honored George Washington

- Liberty Caps

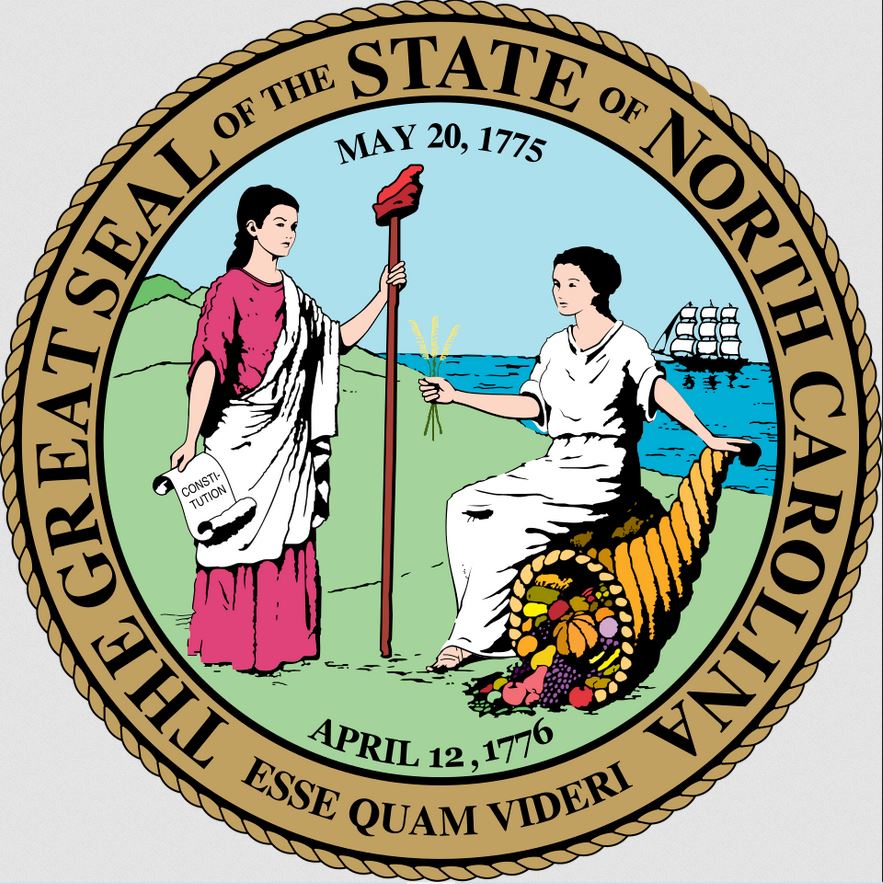

- Capital Of NC (Sort of)

1

The bottle, before cleaning.

2

The front of the A. Dearborn & Co. bottle.

3

The back, with the message “This bottle is never sold”.

4

Dearborn’s mineral water ad, Wilmington Journal, May 7, 1852

Our Blue Mineral Water Bottle

1

The fragments of a chamber pot excavated in Quince Alley by the Public Archaeology Corps.

2

An intact chamber pot in the Musées de la Haute-Saône, in France. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:M0354_1951-45-122_1.jpgAn English humidor, c. 1820, shows a checkerboard pattern achieved by using an engine-turned lathe.

3

William Hogarth’s c. 1738 satirical print “Night”, from the “Four Times of Day” series shows some hazards of nighttime in London. Adding to the commotion of an overturned coach and a festival bonfire in the street, the contents of a chamber pot are poured out of a second-floor window onto the street.

Chamber Pot

1

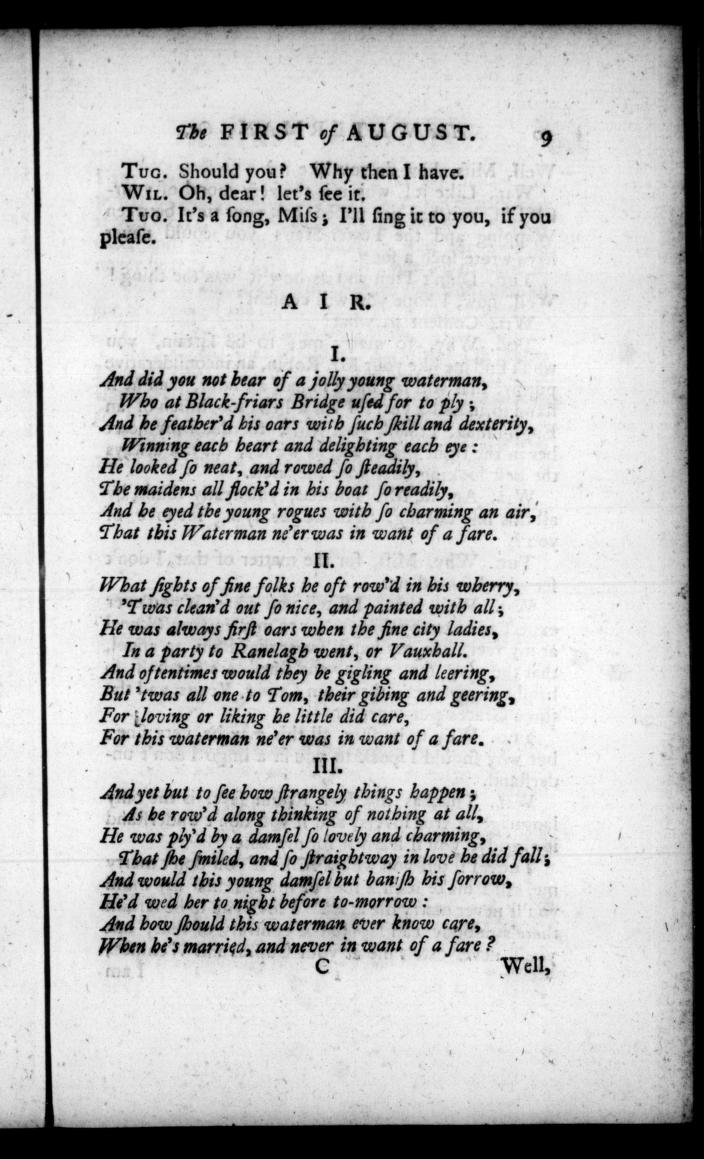

Black transferware fragment, with lyrics from “The Jolly Young Waterman”, written in 1774.

2

The lyrics (which vary slightly from the text on our fragment) from Charles Dibdin’s “The Jolly Young Waterman”, from his comic opera “The Waterman, or, the First of August”.

3

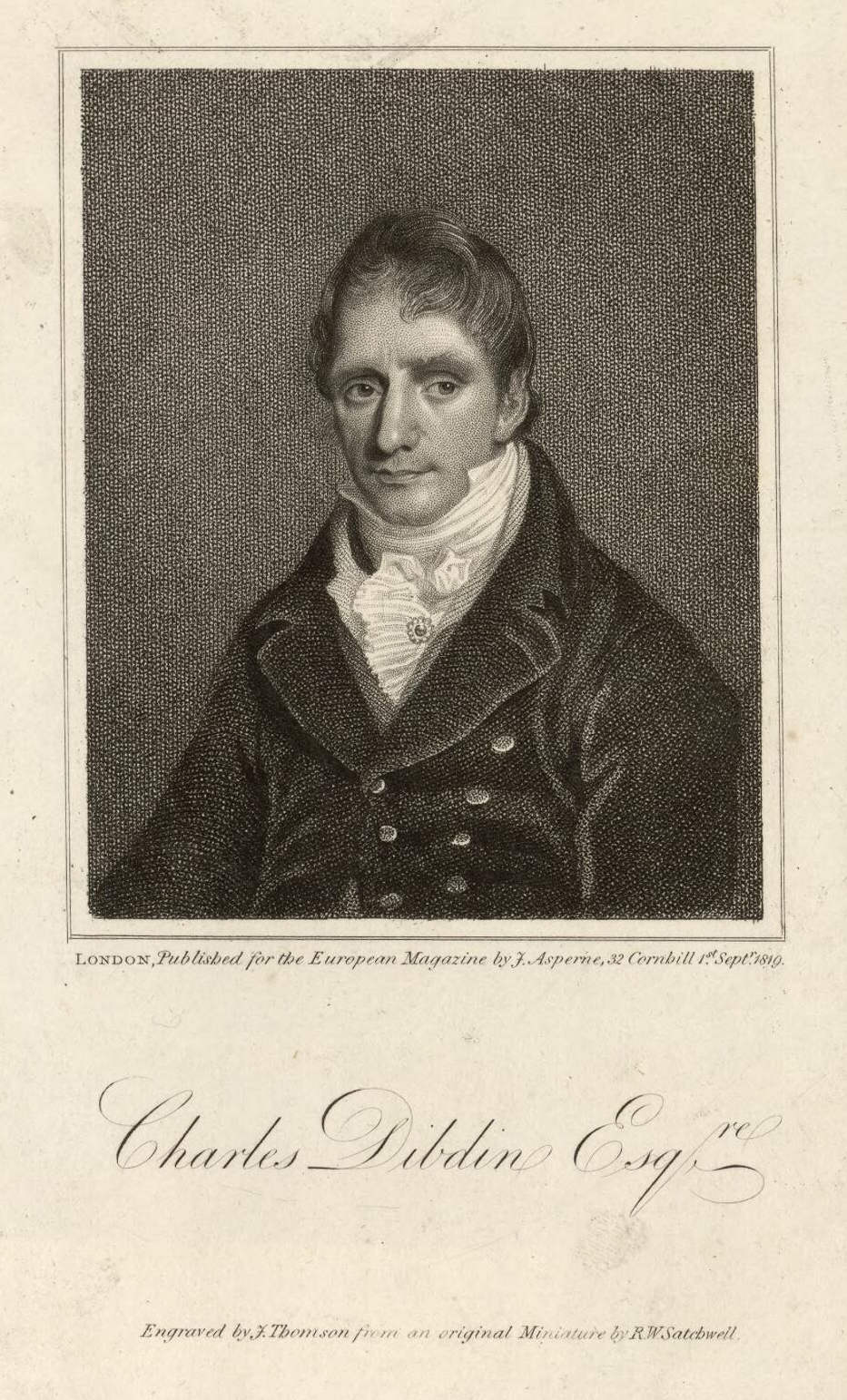

Charles Dibdin, composer of the song lyrics on our ceramic fragment.

4

Musical Fragment of Transferware

1

2

3

Circa 1800, an English mocha ware piece with the familiar moss agate or tree-like pattern made from a mixture containing stale urine and tobacco juice. (Wikipedia.)

4

Mocha ware fragment excavated in our dig near Quince Alley.

5

Mocha ware fragment excavated in our dig near Quince Alley.

6

Mocha ware fragment excavated in our dig near Quince Alley.

7

Mocha Ware in Quince Alley

-

David A. Norris, February 2025

1

A bone button, with one hole.

2

Button from Quince Alley

3

Button from Quince Alley

4

5

6

Front and back of another button blank, with a remnant of a line scored by a button bit.

7

Front and back of another button blank, with a remnant of a line scored by a button bit.

8

A metal button bit, found at the Fort Stanwix National Monument in New York. (National Park Service.)

Bone Buttons and Button Blanks

1

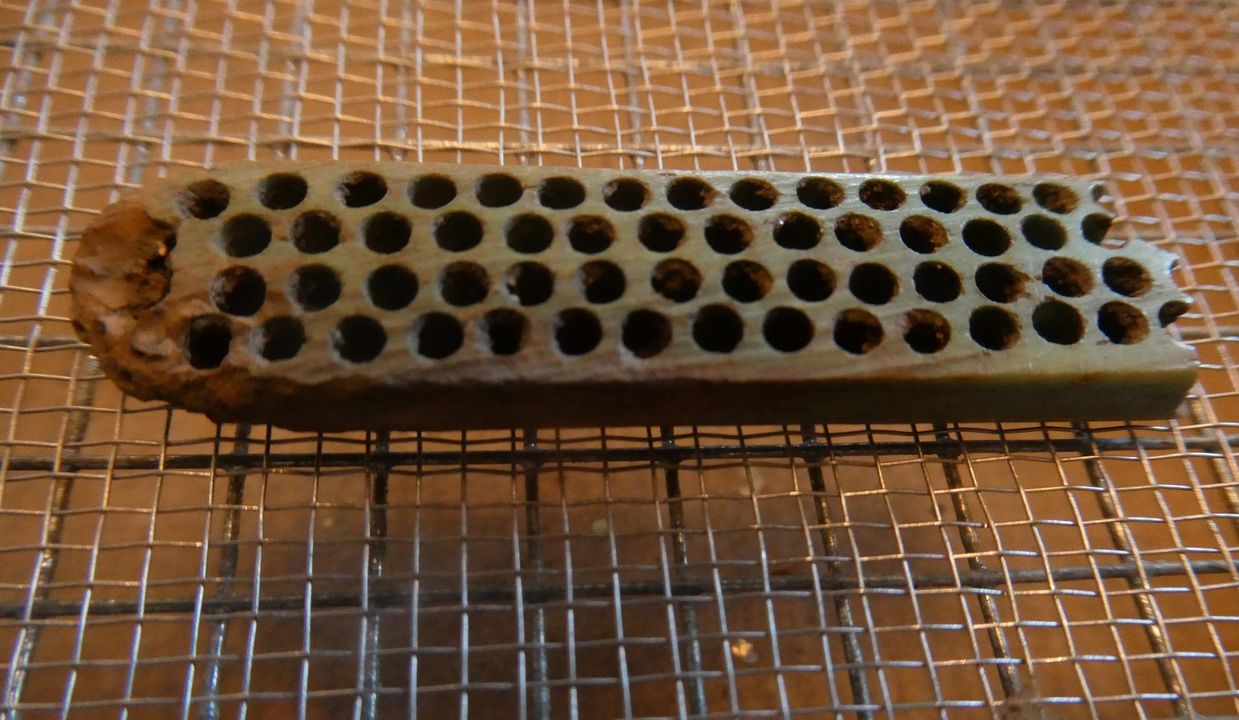

Millstone photo; thanks to Lyle Bass of the Public Archaeology Corps.

2

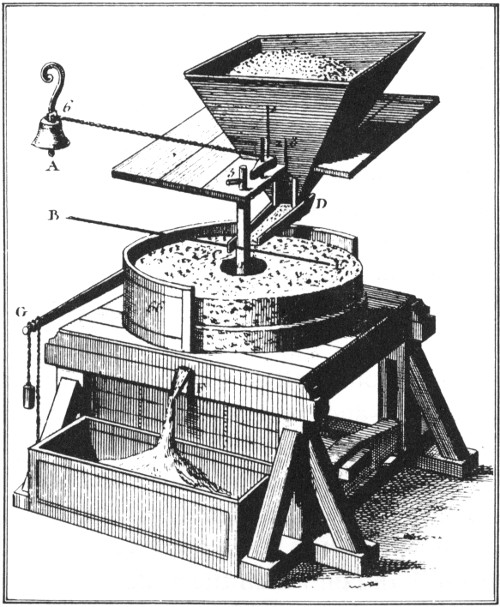

Millstones at work; diagram from Thomas K. Ford, “The Miller in Eighteenth-Century Virginia”. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/58036/58036-h/58036-h.htm

3

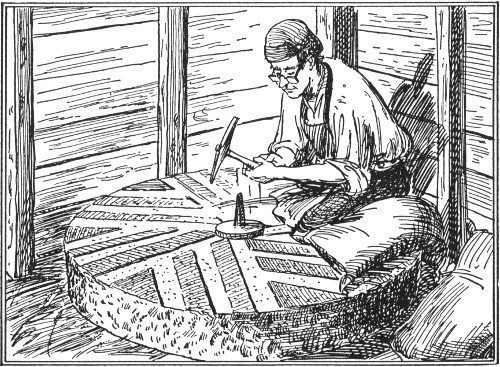

Redressing a millstone, from “The Miller in Eighteenth-Century Virginia”.

4

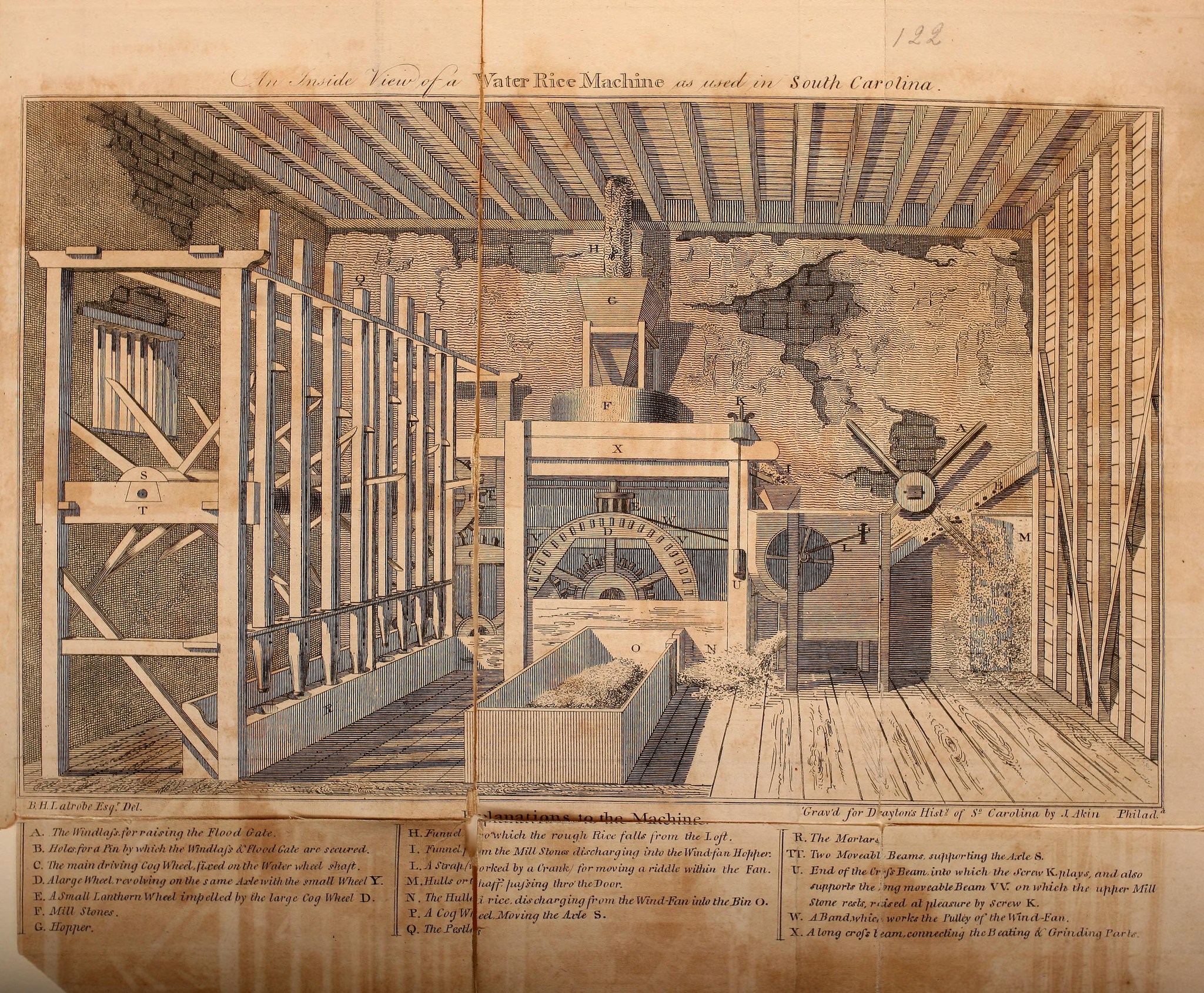

Interior of a rice mill, from John Drayton, “A View of South Carolina”, 1802.

5

Abandoned millstones, Conetoe, Edgecombe County, North Carolina, about 1990.

6

Another view of the millstone at the excavation provided by Barbara Dickinson

A Look at Our Mysterious Millstone

The Public Archaeology Corps’ dig on Quince Alley in downtown Wilmington continues to provide surprises and curiosities. Among the most unexpected recent discoveries, found while digging down into layers of 18th century history, was a millstone! Once, it would have been placed in a grist mill to grind corn or grain.

Grist mills were complex contraptions. Nearly all of the machinery, such as the gears and shafts, was made of wood. The basic technology was quite ancient. Had Chaucer’s 14th century miller from the Canterbury Tales (or for that matter, a miller from ancient Rome) stepped out of a time machine into colonial North Carolina, he would have had little trouble taking over the work in an 18th century mill.

Typically, a colonial American watermill relied on a great wooden millwheel, turned by water power. Undershot wheels turned from water flowing underneath the wheel. Overshot wheels turned from water pouring down on them. Most often, the builder constructed a dam to hold back the water of a stream, and a chute or flume to control the amount of water turning the wheel.

Windmills were placed where favorable winds could turn their sails. An 1810 map of Wilmington notes a windmill standing in the intersection of Fourth and Orange Streets. At that time, that spot would have been at the edge of town, and presumably would have relatively free of tree cover that might interfere with wind power.

So far as 18th century grist mills, those closest to our dig site would seem to have been one that was somewhere around the spot where Market Street crosses Burnt Mill Creek, and another mill at Greenfield Lake. The exact location of “the Burnt Mill” is obscure, but there was a watermill by the dam at Greenfield Lake well into the 20thcentury.

Querns were pairs of small millstones operated by hand. They turn up in some North Carolina probate files of the 1700s. A hand mill would have been useful for a farm family who lived far from a mill. And during summer droughts, watermills had no power to turn the machinery, so a hand mill could provide a temporary supply of corn meal.

Millstones were matched in pairs. The lower, called the bedstone or set stone, was fixed in place. The upper, called the runner stone, was the only one that rotated. Fixed to the top of the main shaft was an iron fitting called the rind (or rhynd). Carved slots on the face of the running stone allowed it to fit onto the rind, allowing the running stone to rotate when the shaft turned.

Grain poured down from a hopper through a hole in the center of the running stone. Both of the facing sides of the millstones were carved with grooves, called furrows. Spaces between the furrows, which were called lands, were smoothed flat. As the stones rotated, centrifugal force threw ground meal outward. The millstones were enclosed in wooden casing, so the flying meal was deflected down into a bin.

Millers kept small but precise gaps between the millstones, for the most efficient grinding of various products. If the grain supply ran out, friction between the stones could create enough heat to start a fire. Some mills had a bell rigged up to ring if the grain bin feeding the stones was empty.

Millstones wore down constantly, so they required frequent re-dressing (re-cutting the furrows to deepen them). Typically, a stonecutter came to the mill to re-dress the stones. New millstones were made one foot thick or more, and could weigh well over 1000 pounds. Each session of re-dressing represented a quarter of an inch or so of surface worn down from the stones. Eventually the stones wore down so much they had to be replaced.

In the Piedmont and mountain regions of North Carolina, there was plenty of suitable stone for millstones. In our sandy Coastal Plain, colonial millers depended on stones imported from England or Europe.

Mills tended to have multiple pairs of stones. Imported from the Rhineland in Germany, “Cullen” or “Cullin” millstones were made of basalt, usually of a dark grey or blue. The name Cullen was derived from the city of Cologne, near the millstone quarries. These German millstones were used for grinding corn. French “buhr” or “burr stones”, which were made from a type of chert or flint, were more expensive. They were prized for grinding wheat. Most millstones were a single large stone, but French buhr stones were usually made from several pieces that were fitted and cemented together, and bound by an iron rim. Other stones were made of “millstone grit”, a suitable grade of sandstone found in England and elsewhere.

Some wheat was grown in North Carolina, but “Indian corn” was the most common commodity for grist mills. A number of rice mills operated along the lower Cape Fear. In the 19th century, steam engines let millers set up anywhere. Several large steam-powered mills were built along Wilmington’s waterfront. North Carolina’s windmills disappeared, but many water-powered grist mills ran well into the 20th century. My father’s family took their corn to a water mill in Wake County as late as the 1940s.

The records of Port Brunswick (a customs district based in Wilmington after 1776) note a few shipments of millstones. The ship Commerce brought 24 millstones from Whitehaven, Nova Scotia in 1774. Merchant John Burgwin, the original owner of the Burgwin-Wright House at 3rd and Market Streets, shipped three pairs of millstones from Philadelphia on his sloop Experiment in 1774. In 1787, the ship Queen of Francebrought a cargo including six pairs of millstones from Baltimore for Burgwin. The schooner Dispatch arrived here from Philadelphia in 1788, with a large cargo including “Sundry Wood Work for a Mill”.

How did our millstone end up, way down in Level 11, on our site? In colonial times and later, the permission of the New Hanover County Court (a.k.a. the Inferior Court of Pleas and Quarter Sessions) was required for building a public grist mill. There seem to be no records of a mill standing anywhere nearby. That said, however, the county court minutes between early 1742 and 1759, and for 1770 and early 1771, are missing. Unless our millstone was associated with a forgotten mill, it would appear to have been dropped, placed, or dumped there at some point. More digging and investigation should provide some context to shed some light on the mysterious millstone.

PAC Historian, David Norris

shares stories of

artifacts found

during Lab work.

1

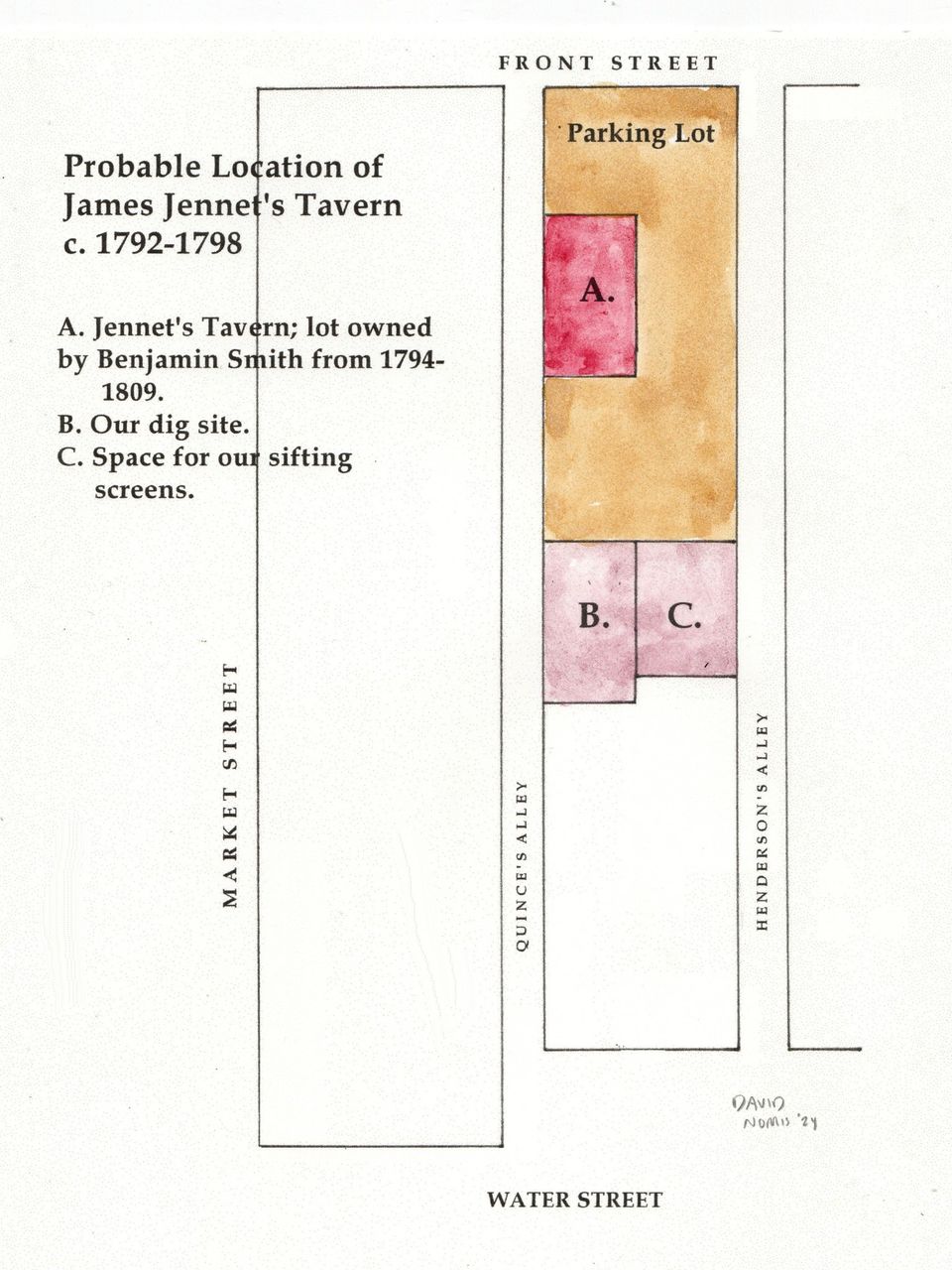

The approximate site of Jennet’s Tavern, c. 1792-1798.

2

Benjamin Smith, owner of the Jennet’s Tavern lot from 1794-1809.

3

10-12 Front Street about 1902.

4

The dig site and parking lot area, 1915 Sanborn Insurance Map.

James Jennet’s 1790’s Tavern

Quite a few of the artifacts found in our dig with the Public Archaeology Corps on Quince’s Alley — bowls and stems of clay tobacco pipes; shards of possible wine or liquor bottles; and fragments of plates, bowls, cups, and glasses – are the sort of artifacts excavated from tavern sites. And, indeed, surviving records of Wilmington and New Hanover County indicate that as many as five (or more) taverns, ordinaries, or bars may have operated near our dig site between the 1750s and the 1840s.

Technically, an ordinary was a combination bar-restaurant-hotel, with stabling for the horses of overnight guests, while a tavern was a bar that might also serve food. In practice, people often used both terms interchangeably. Ordinaries and taverns in colonial and later New Hanover County required annual licenses from the county court.

One of the taverns near our dig site was run by James Jennet. The New Hanover County Court first granted him a license to keep an ordinary in Wilmington in 1792. Surviving county court records show that he renewed his license at least twice, in 1793 and 1796.

A February 22, 1798 ad in Hall’s Wilmington Gazette noted that there was a town house for sale “in Quince’s alley, which has long been occupied by James Jennet, and in use as a well frequented Tavern, the same having been lately repaired.” Unfortunately, Jennet’s Tavern was destroyed with practically the whole block in a fire on April 21, 1798. Jennet never renewed his tavern license after the fire.

In 1768, John Quince bought the lots along both sides of Quince’s Alley, from Front Street to the river. Soon after, he sold several parcels, including a lot running 42 feet along the south side of Quince’s Alley. The approximate position of the lot in the 1769 map of Wilmington by Joseph-Claude Sauthier shows a building, tinted in red watercolor on the map. The red tint is believed to represent brick buildings on the map.

At some point soon after 1768, William Evans obtained this 42-foot lot from Quince. Evans sold it to Peter Brown in 1778. A suspected Loyalist during the Revolutionary War, Brown suffered the confiscation of property by the patriot government. This lot changed hands a few times before Benjamin Smith bought it in 1794. Apparently, Smith rented the property to Jennet for use as a tavern. It was not uncommon for a house to be converted into a tavern, and the tavern keepers often lived in the same building.

The newspaper ad listing the tavern building for sale was among several placed by Benjamin Smith. Later serving as governor of North Carolina in 1810-1811, Smith owned Belvedere Plantation in Brunswick County, among numerous other lands. But, he only owned one lot on Quince’s Alley. Written records provide enough clues for us to know where this tavern stood.

The old Jennet’s Tavern place was evidently not rebuilt by April 15, 1806, when Smith offered his lot on Quince’s Alley for sale in the Wilmington Gazette. It took him until 1809 to sell it, when it was purchased by Col. Thomas Cowan. Later deeds for surrounding lots indicate that a lot on the northeast corner of Quince’s Alley and Front Street ran 28 feet west along the south side of the alley, where it joined the edge of the “42-foot lot”.

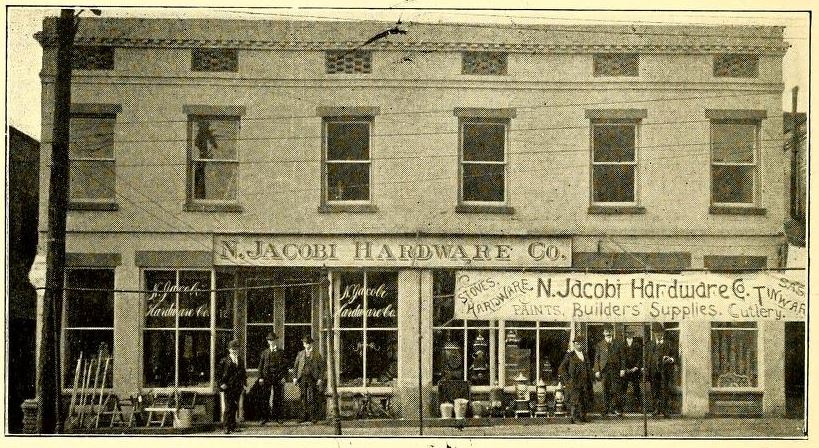

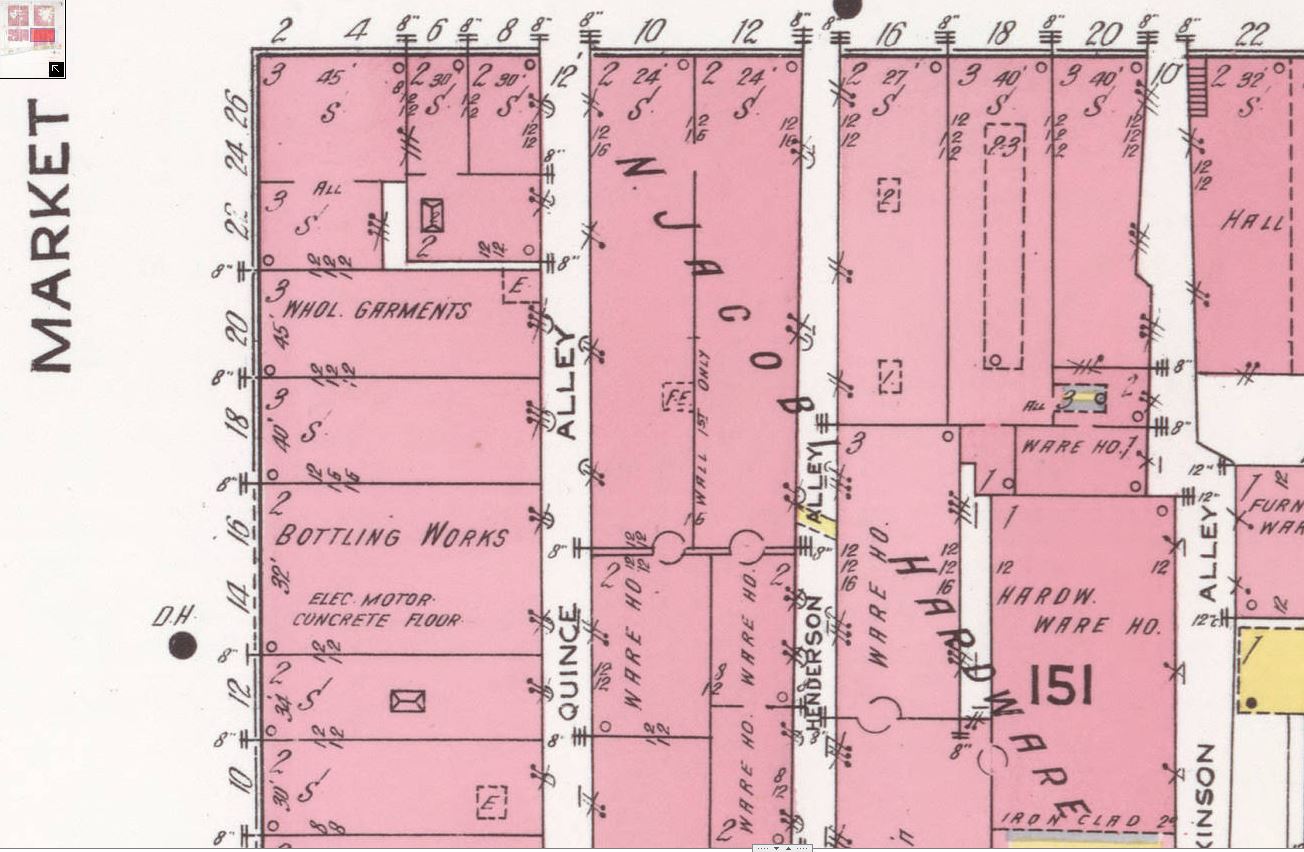

After Thomas Cowan died, the “42-foot lot” had several owners before another fire swept the block in 1845. New buildings appeared on the property. After the Civil War, a grocery store and a saddle and harness shop stood nearby on Front Street. The Jacobi Hardware Company moved there in 1870, and by 1901, that company owned the property between Quince’s and Henderson’s Alleys, running 117 feet back from Front Street to the walls of the brick buildings where Public Archaeology Corps is now working. Their hardware store and warehouse space filled the lot, covering up the former site of Jennet’s Tavern. Before World War II, the Jacobi Hardware Company moved out of 10-12 South Front Street, and the space was occupied by a men’s clothing shop and a jewelry store. After a fire in 1984, the damaged buildings were demolished and the site became the parking lot we see today.

1. The approximate site of Jennet’s Tavern, c. 1792-1798.

2. Benjamin Smith, owner of the Jennet’s Tavern lot from 1794-1809.

3. 10-12 Front Street about 1902.

4. The dig site and parking lot area, 1915 Sanborn Insurance Map.

1

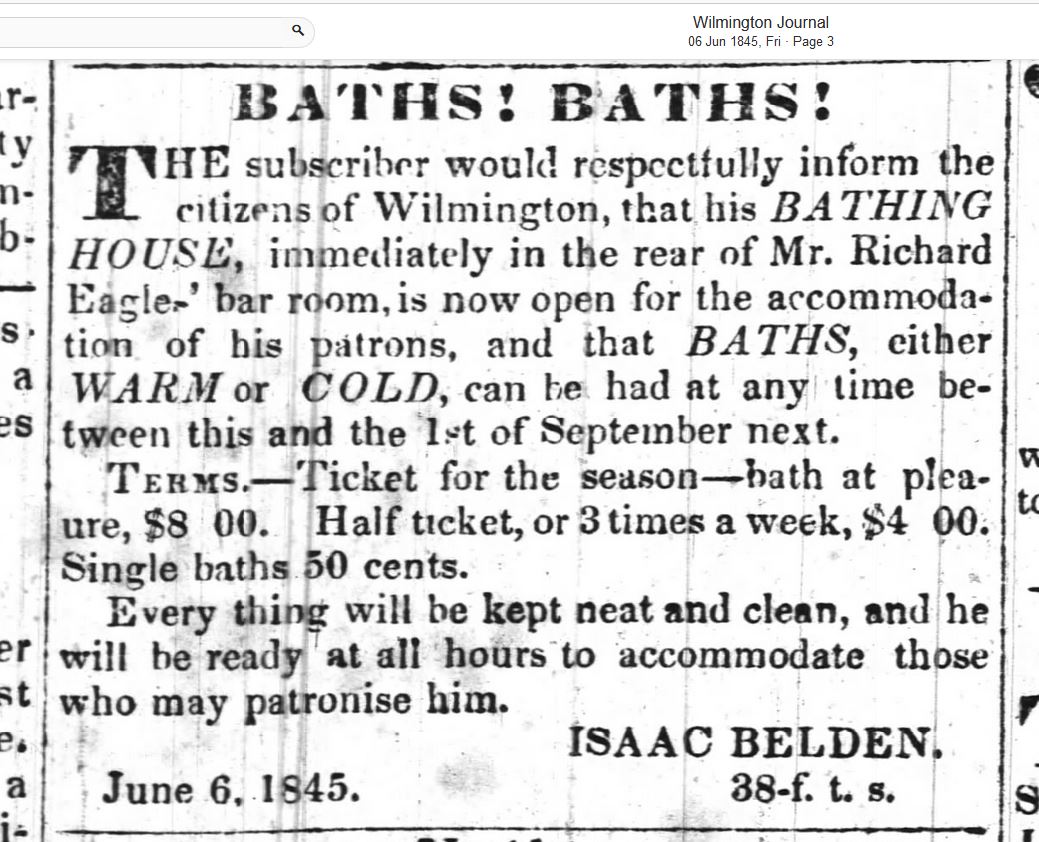

One of Isaac Belden’s ads for the bathing house on Quince’s Alley (Wilmington Journal, June 6, 1845)

2

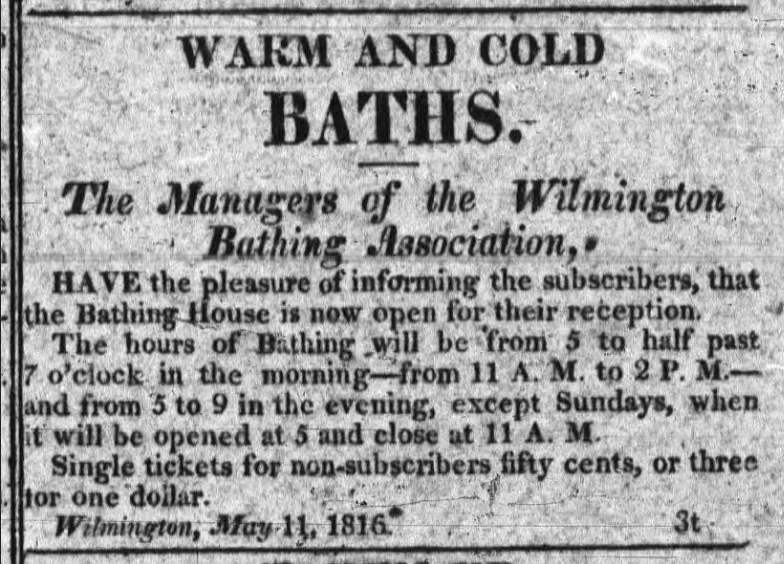

Ad for the Wilmington Bathing Association (Cape-Fear Recorder, May 20, 1816).

3

Ad for the Seventy-Six Coffee House (Cape-Fear Recorder, April 13, 1825).

4

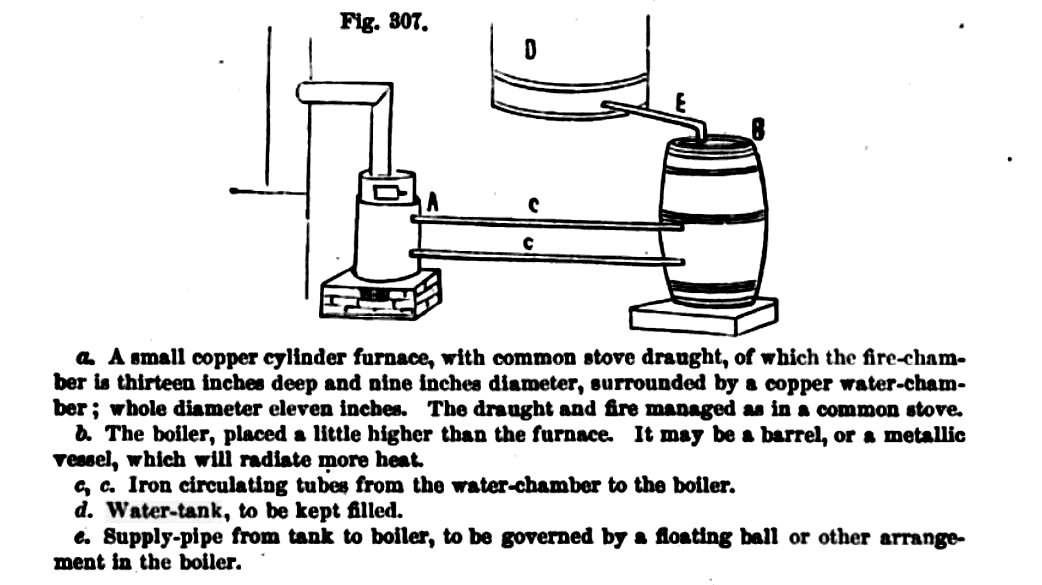

A system for heating water at home; perhaps Isaac Belden had something like this installed at his bathing house on Quince’s Alley. (Alexander Watson, American Home Garden. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1859.)

Bathing Houses in Old Wilmington

In 1842, an emancipated former slave turned businessman named Isaac Belden opened an oyster house on Quince’s Alley, where the Public Archaeology Corps has conducted a dig since 2019. As summer 1843 approached, with the cool-weather oyster season at an end, Belden advertised a new enterprise, a bathing house.

The Clarendon Water Works (Wilmington’s first water plant) didn’t provide citywide running water until 1881. It was possible (although expensive) to bring running water into an antebellum house, from a water tank, fed by water pumped from a well or cistern. But, for most households, hauling water inside and heating it up to pour into a bathtub took a great deal of time and effort.

Belden’s was not the first public bathing house business in town. The Wilmington Bathing Association opened a bathing house on Front Street in May 1816. They were open daily from 5 a.m. to 7:30 a.m.; 11 am to 2 pm; and 5 to 9 pm; except Sundays, when they were open from 5 a.m. to 11 a.m. Non-subscribers could get a bath for 50 cents, or bathe three times for one dollar.

In the 1840s Belden also charged 50 cents for one bath. He offered a “ticket for the season” for $8, with as many baths as one wanted, or a $4 “half ticket”, which allowed three baths a week during the season.

The “Old ‘76” tavern and hotel building stood on the east side of Front Street between Orange and Ann Streets. In 1819, owner Dominique Cazaux added bathing rooms to the business, which already included a coffee house, bar room, reading room (with a library of out-of-town newspapers), hotel rooms, and a stable. The Verandah Saloon, on the southeast corner of Water Street and Wilkinson’s Alley, added a bath house staffed with attendants in 1849.

By 1856, the “eating saloon” at the city’s Wilmington & Weldon Railroad Depot had “a number of bathing rooms, elegantly fitted up for warm or hot baths”, according to the Wilmington Journal.

Little detail was given in the Wilmington papers about the set-up of the 1800s bathing houses. One might expect water tanks; tubs; pumps; drains; and some sort of furnace or heating source for the water. In Savannah, Georgia, an 1850 fire was thought to have started in a bathing house “with stoves and other apparatus for heating water”, according to the Wilmington Journal.

In 1870, the contents of a shaving saloon at Front and Princess were offered for sale. Among the items were “4 Bath Tubs, Faucets and Fixtures, 3 Marble Slabs, 1 Centre Table, 1 Square Table, Towels, Aprons, &c.”

Wilmington’s most elaborate bathing establishment was certainly J. W. Spaulding’s Floating Bath House. Opened in 1870, the bath house was built on a flatboat anchored near the ferry dock at the foot of Market Street. Two 10 x 30-foot wings, enclosed on the sides and bottom by lattice work, held bathers safely in a sort of pool about 3 to 5 feet deep. Changing rooms were built on the flatboat, and a large roof covered the whole thing.

The Floating Bath House was more for swimming than bathing for cleanliness. The downtown riverbank itself attracted bathers during the 1800s. Whether trying to keep clean or cool off on hot summer days, quite a few 19th century skinny-dippers were arrested at Greenfield Pond, or along the river downtown between Harnett and Castle Streets. Another problem was that people took baths in the Rock Spring at the foot of Chestnut Street – which was a source of drinking water for people living in that part of town!

Illustrations: 1. One of Isaac Belden’s ads for the bathing house on Quince’s Alley (Wilmington Journal, June 6, 1845). 2. Ad for the Wilmington Bathing Association (Cape-Fear Recorder, May 20, 1816). 3. Ad for the Seventy-Six Coffee House (Cape-Fear Recorder, April 13, 1825). 4. A system for heating water at home; perhaps Isaac Belden had something like this installed at his bathing house on Quince’s Alley. (Alexander Watson, American Home Garden. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1859.)

1

A batch of pipe stems found at the Quince’s Alley dig, after cleaning in the PAC Lab.

2

Tobacco pipe ad in the American Weekly Mercury (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), May 12, 1720.

3

An ad for a Wilmington merchant selling “tipt pipes” (tipped with glaze or wax) and short pipes. North Carolina Gazette (Wilmington), April 6, 1797.

4

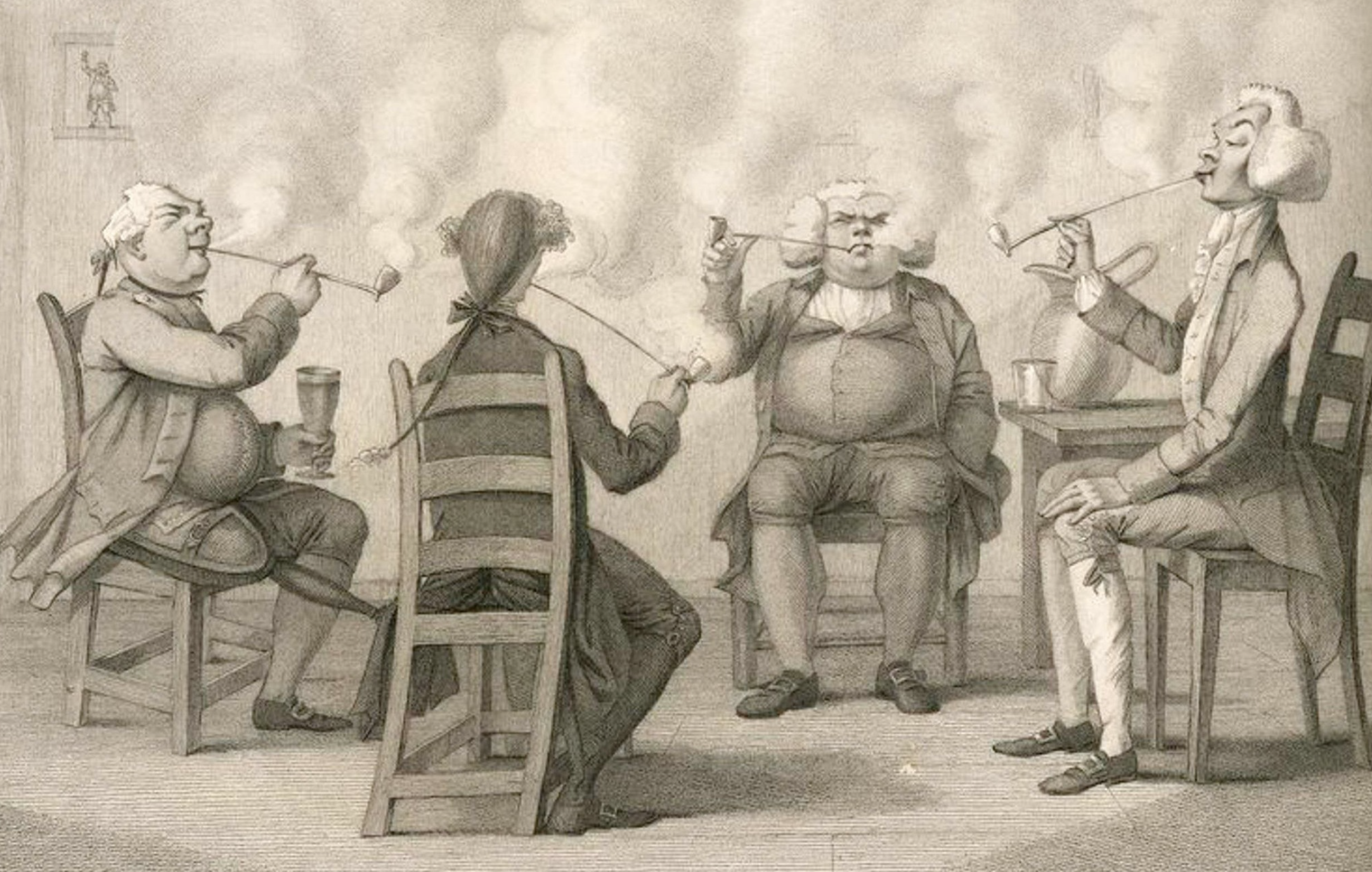

Smokers with long-stemmed 18th century tobacco pipes; a detail from William Hogarth’s 1733 engraving “A Midnight Modern Conversation”.

5

English gentlemen, smoking long-stemmed clay tobacco pipes in a satirical 1792 print. (NY Public Library.)

6

Part of a maker’s mark on a pipe stem fragment.

7

A fragment of a pipe stem, giving us a cross-section.

A Look at Clay Tobacco Pipes

Among the trove of artifacts recovered by the Public Archaeology Corps’ dig on Quince’s Alley in downtown Wilmington are untold hundreds of fragments of clay tobacco pipe stems and bowls. Large quantities of pipe stem and bowl fragments are often found near tavern sites, and we know from various records that there were several taverns or bars on Quince’s and Henderson’s Alleys near our dig site between the 1750s and the 1840s. Tobacco pipe fragments can give clues to dating the deposits they’re found in, and tie the port of Wilmington into the wider world of 18th century trade.

Tobacco was native to the “New World”, and American Indians used tobacco for thousands of years before Spanish ships carried it to Europe in the mid-1500s. English settlers of “the Lost Colony” found tobacco in North Carolina in the 1580s, but tobacco was already well-known in England by that time. In the early 1600s, commercial production of tobacco began in the Jamestown colony in Virginia.

English manufacturers began churning out tobacco pipes in the Elizabethan era. Dutch factories also produced pipes, and pipes were made in Philadelphia by the late 1600s. Cigars didn’t catch on until the mid-1800s, and cigarettes only became popular after the Civil War. Until then, nearly anyone who smoked tobacco used a pipe.

Hundreds of factories in England produced pipes. Women worked in many of them, and some women owned pipe factories and placed their own makers’ marks on them.

To make pipes, workers rolled out a long piece of clay to shape the stem, adding a blob at one end to create the bowl. Lengthy stems, often about one foot long, were a distinct feature of pipes of the colonial era and later, although short pipes were also advertised and sold.

Once the pipe was shaped, a metal wire was carefully poked through the stem to create the bore. Next, the damp clay was squeezed into a mold. A cone-shaped metal bit pressed into the end of the pipe to make the bowl.

Little dies with letters or symbols, not unlike the hallmarks used to mark silverware, were pressed into the clay to create unique maker’s marks. Many marks are well-documented, and can be tied to the location and dates of operation for a pipe factory.

When dry, the pipes were taken out of the molds and smoothed out before being dried for three days or so. Then, the pipes were fired in a special pipe kiln. For special “tipped pipes”, a dab of glaze was added to the end of the stem before firing, so the clay would not stick to the lips of the smoker. Some pipes were tipped with wax.

Despite the labor involved, clay pipes were very cheap. In 1720 a Philadelphia tobacco pipe maker named Richard Warder offered a gross of pipes (12 dozen) for only four shillings. At that rate, customers got three dozen pipes for one shilling, or three pipes for a penny. Buying more than one gross at a time dropped the price to three shillings.

Pipes were fragile enough to break easily, and cheap enough to replace. After some use, pipes could become clogged with “tar”, or tobacco residue. Rather than throw away the pipe, though, many smokers set the pipe in a hot fire to burn away the accumulated tar. In his 1720 ad, Richard Warder let customers know they could have their “foul Pipes burnt” in his kiln for eight pence per gross.

The shapes and styles of pipe bowls and stems offer clues for dating them. Another way of dating pipe fragments is by the diameter of the hole in the stem. The holes in English pipe stems consistently became narrower from the late 1600s until well into the 1700s. Until changes in the pipe-making industry near the end of the 18th century spoiled this neat progression, the width of the holes in the stems is a very useful dating measure.

Surviving 18th century records of the Port of Brunswick (an administrative area that covered colonial and federal-era Wilmington, Brunswick Town, and the plantations and landings on the Cape Fear) mention pipes in the cargo of incoming vessels.

Among the local merchants named as receiving shipments of tobacco pipes was John Burgwin. He once owned the Burgwin-Wright House, which stands today at Third and Market Streets. Records of Port Brunswick show that Burgwin received consignments of pipes aboard an unnamed brig from Bristol, England in 1773; from England in the brig William in 1774; and in a sloop from New York in 1789.

1

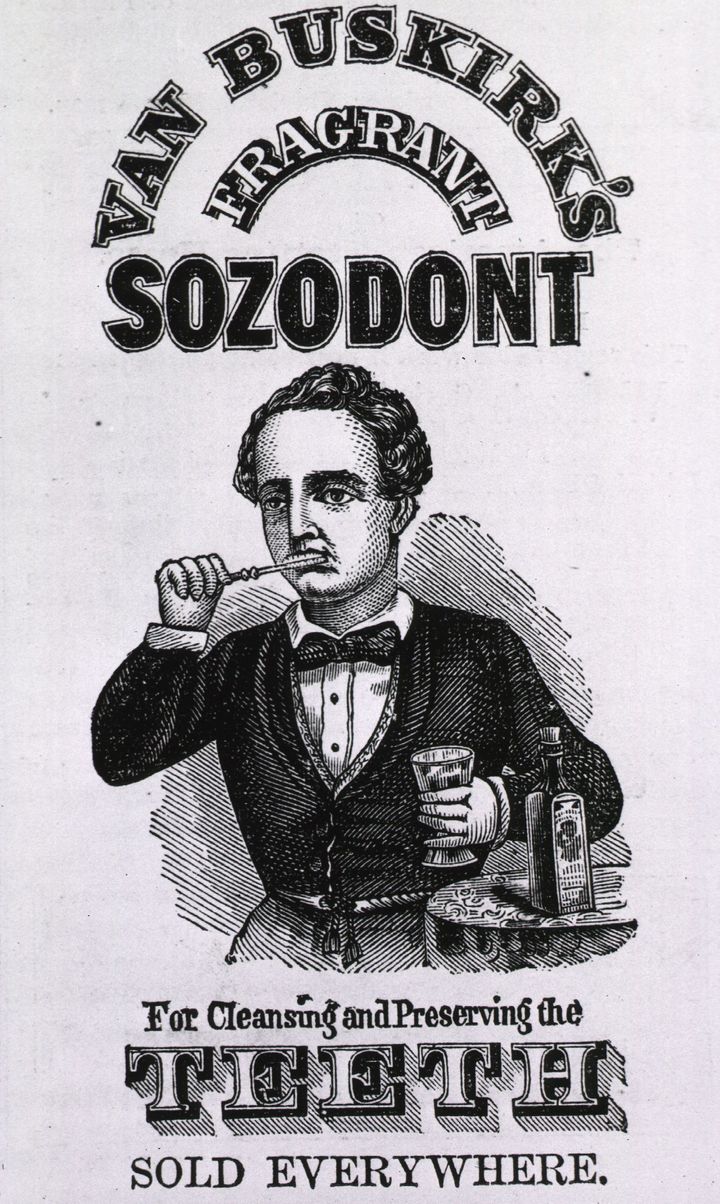

A toothbrush ad, from Harper’s Weekly (New York), July 6, 1867.

2

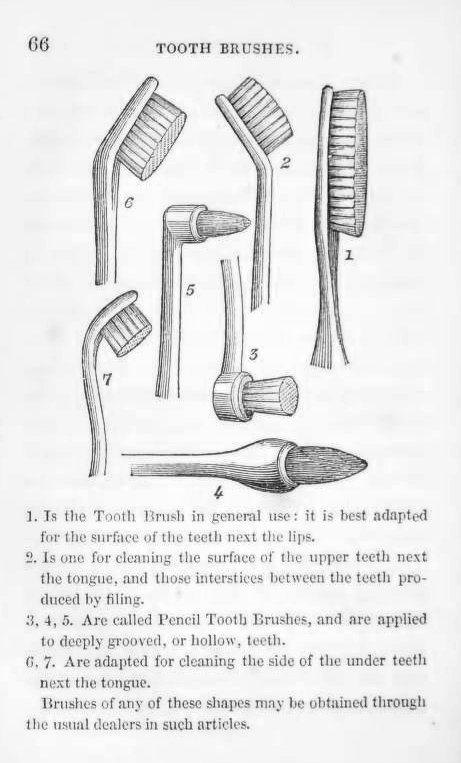

Toothbrush styles from D. A Cameron, Plain Advice on the Care of the Teeth … (Glasgow, 1838).

3

Wilmington merchant W. Ware advertised toothbrushes for sale, in the Wilmington Tri-Weekly Commercial, March 3, 1847.

4

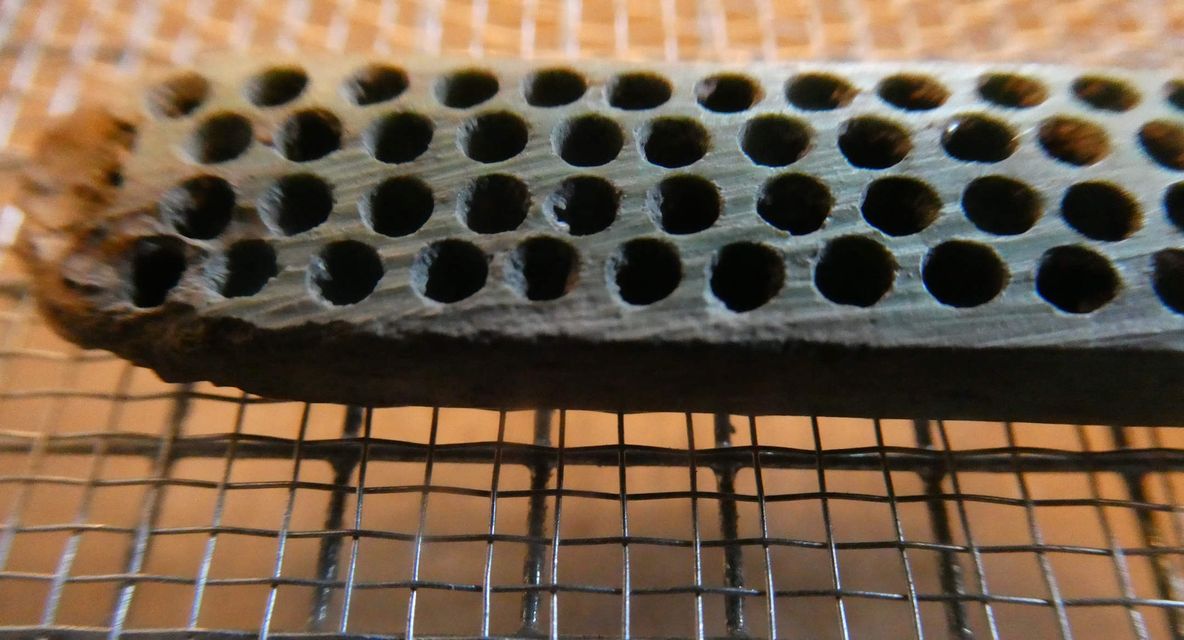

The front of our toothbrush.

5

The front of our toothbrush.

6

The back of our toothbrush, showing the slots cut to connect with the holes drilled from the top to hold the bristles.

7

The back of our toothbrush, showing the slots cut to connect with the holes drilled from the top to hold the bristles.

The Toothbrush Found by Quince’s Alley

One of the most interesting artifacts recently cleaned in the Public Archaeology Corps’ lab is a part of an early toothbrush. By its style, and the level it was found, it likely dates from the mid-1800s. The block where we are digging on Quince’s Alley in downtown Wilmington was last swept by fire in 1845, so perhaps the toothbrush dates from about that time.

Our example appears to be made of bone, with a pale green paint of some sort applied to it. It was quite common to use bones, such as a piece of a cow femur, to carve into toothbrushes in the 18th and 19thcenturies. Various artificial materials appeared in toothbrushes in the late 1800s, but bone was still used for the handles well into the 1900s.

The handle of our toothbrush was broken off, but the head contains four rows of tiny and regularly spaced holes. Slight variations in the spacing show the holes were drilled carefully by hand one at a time; machinery to drill more precise holes was introduced some years after the Civil War.

Turning the brush head over, one sees four very finely-cut straight grooves, dug in just deeply enough to connect with the holes from the top. Hog bristles were commonly used in toothbrushes then and later. The grooves cut in the bottom of the toothbrush allowed the bristles to be secured and woven to the brush.

In 1846, Wilmington merchant W. Ware sold toothbrushes for 25 cents each. For the same price, you could buy boxes of “Tooth Wash or Tooth Powder of the best description” for 25 cents. Wilmington druggist W. H. Lippitt offered toothbrushes made in America, France, and England in 1855.

A January 11, 1823 recipe for tooth powder in the New England Farmer included some interesting ingredients:

2 parts Peruvian bark (the bark of the cinchona tree, the source of quinine);

4 parts Armenian bole (a kind of clay)

4 parts prepared chalk (finely ground and purified chalk)

2 parts myrrh (a fragrant resin extracted from small thorny trees native to parts of the Arabian Peninsula and the Horn of Africa).

2 parts loaf sugar

½ part carbonate of soda

2 parts Castile soap (an olive oil-based soap from Spain)

The New England Farmer advised, “The mouth should be rinsed with cold water, and the brush dipped into it before the powder is used. A quantity of the powder should then be taken up on the end of the brush, and applied to every part of each tooth … The best time for using the tooth powder is after breakfast, and this should be done every day. In addition to this, we should be careful to cleanse the mouth with water and the brush, after every meal …”

Many 19th century people did not bother with toothbrushes. Cultural historian Kerry Segrave estimated that even in 1920, only one in four Americans owned a toothbrush. A British officer, Col. Arthur Cunynghame, published a memoir of a tour of the United States in 1852. The colonel was horrified to see hanging in the washrooms of American steamboats, “a common tooth-brush … chained to the wall for general use!”

1. A toothbrush ad, from Harper’s Weekly (New York), July 6, 1867.

2. Toothbrush styles from D. A Cameron, Plain Advice on the Care of the Teeth … (Glasgow, 1838).

3. Wilmington merchant W. Ware advertised toothbrushes for sale, in the Wilmington Tri-Weekly Commercial, March 3, 1847.

4 and 5. The front of our toothbrush.

6 and 7. The back of our toothbrush, showing the slots cut to connect with the holes drilled from the top to hold the bristles.

1

An 18th or 19th century tapered case bottle, from the Metropolitan Museum, New York City.

2

Small case bottles fit into wooden cases. This elegant English piece contained a set of drinking glasses and a mirror. (Metropolitan Museum of Art).

3

A fragment of the base of a case bottle, found in our dig on Quince Alley.

4

The base of an “apothecary bottle”; such bottles could fit in apothecary chests used by druggists, doctors, and families.

5

The base of an “apothecary bottle”; such bottles could fit in apothecary chests used by druggists, doctors, and families.

6

The crew of the notorious pirate Blackbeard made grenades out of case bottles filled with gunpowder.

Bottles

A look at some of the glass fragments we’ve found, starting with bits of case bottles and “gin bottles” ….

At the Public Archaeology Corps’ dig by Quince Alley in downtown Wilmington, we have certainly found lots of fragments of 18th and early 19th century bottles. Many of these pieces have a square base. Rather than being curved like most bottles, some were made with four straight sides with slightly rounded corners. Other bottles had four sides, but were slightly tapered from the square base. Known as “case bottles”, and made in a variety of sizes and types, they were indeed perfect for shipping in crates and chests.

Case bottles were hand-blown in a laborious process. The main part was blown into a square mold to shape it. Sometimes, wooden molds were used; they had to be kept wet to avoid the molten glass from setting them on fire. The neck and shoulder were created in a separate step, and added to the main part of the bottle while the glass was still in a partially molten state. A tapered bottle was easier to remove from the mold.

Apothecary chests, wooden boxes with small compartments to hold case bottles of medicines, are found in many museums and antique shops. Similar boxes, intended to hold a selection of liquor bottles, were crafted with elegant style and had a compartment for a set of drinking glasses. Some British or American officers carried such boxes of case bottles on military campaigns.

Larger case bottles (often of dark green glass) are sometimes called “Dutch gin bottles”, although they were used for other products as well. (At any rate, “gin” bottles would have been washed and reused many times, and might have held several different liquors before they were broken and discarded.)

Gin, typically a grain-based liquor primarily flavored with juniper berries, became popular in the 17th Netherlands. Often the drink was called “Geneva”. There was no connection with Geneva, Switzerland; “Geneva” was an anglicized version of the Dutch word jenever, for “juniper”.

Although rum and wine usually arrived in North America in gigantic wooden casks, gin normally crossed the Atlantic in case bottles packed in wooden crates. Records of Port Brunswick (a customs district including Brunswick Town, Wilmington, and various Cape Fear River landings) record a great many crates of gin arriving in Wilmington during the 1780s. The actual place of manufacture doesn’t appear in the books, but the customs officials wrote where the cases of gin were shipped from.

In the years 1784-1789, Port Brunswick records show at least one large shipment of 70 cases of gin direct from Rotterdam in the Netherlands. Thousands more bottles of gin came from the Dutch colonies of St. Eustatius and Curacao; the French possessions of Guadeloupe and Martinique; the British colony of Antigua; St. Bartholomew (a former French colony in the Caribbean, which was ceded to Sweden in 1784); and the American ports of Charleston, New York, and Boston.

By a rough count of the Port Brunswick records, in the calendar year 1789 alone, 267 cases of gin were unloaded. That would be 3,204 bottles if the cases held one dozen each. Much of this gin was likely sold on to merchants in Fayetteville and elsewhere in the region.

Empty bottles were valuable enough not only for reuse, but for shipping to other ports. A shipment of five crates of empty gin bottles arrived at Port Brunswick from Rhode Island in 1789. Some merchants advertised for bottles. In 1787 merchants John and Thomas Read of Boston, for instance, offered “Cash given, for empty bottles and gin juggs”. For that matter, merchants might also buy the empty gin crates as well.

The notorious pirate Edward Thatch or Teach, aka “Blackbeard”, found another use for case bottles. According to an early 18th century account, when his ship was attacked by a detachment of the Royal Navy at the Battle of Ocracoke Inlet in 1718, the pirates “threw in several new-fashioned sort of grenadoes; that is, case-bottles filled with powder and small shot, slugs, and pieces of lead and iron, with a quick-match [fast-burning fuse] in the mouth of it …” However, the case bottle grenades did not save Blackbeard from being killed, nor did they prevent the capture or death of his entire crew.

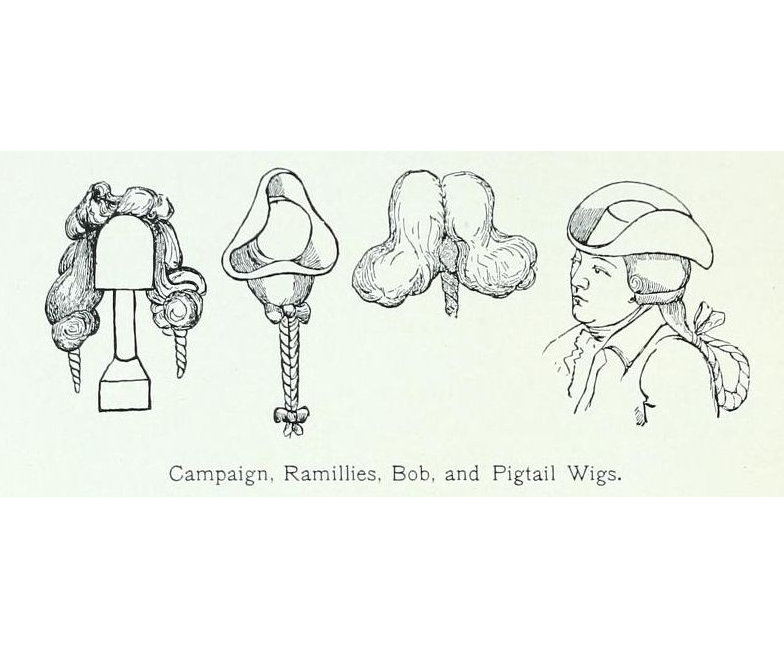

1

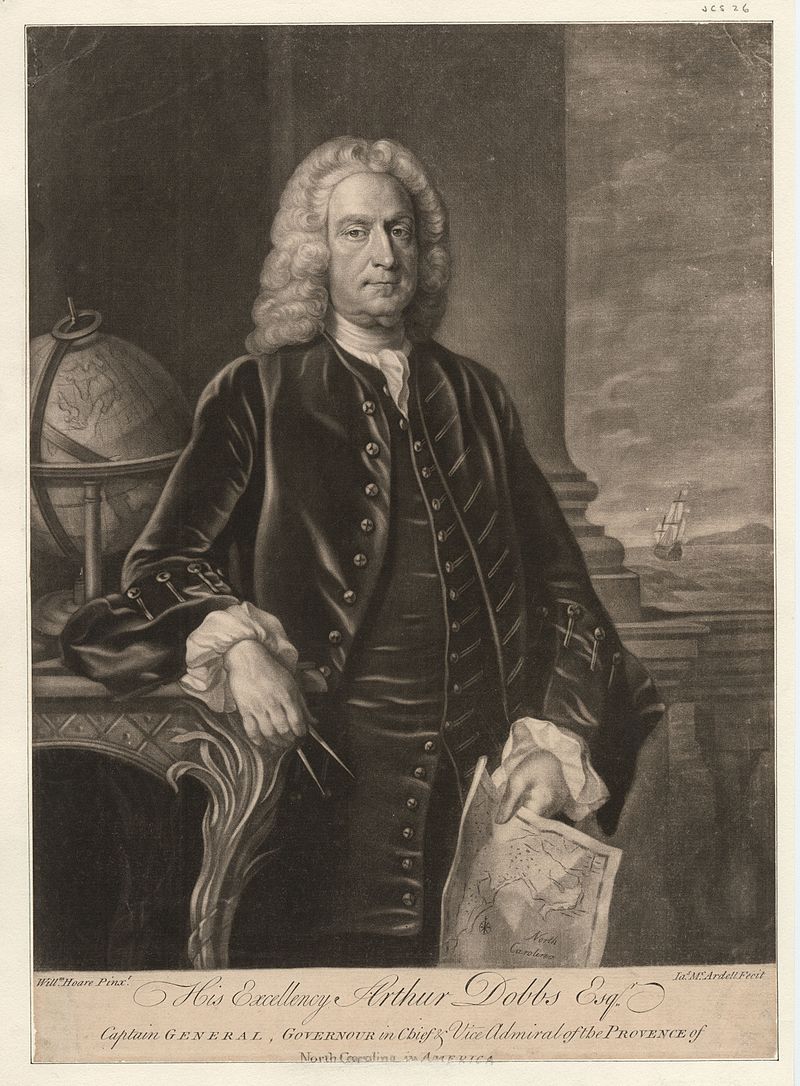

Gov. Arthur Dobbs of North Carolina, wearing a wig.

2

Types of 18th century wigs.

3

The wig curler fragment found in the Quince Alley dig.

4

What the wig curler might have looked like unbroken.

5

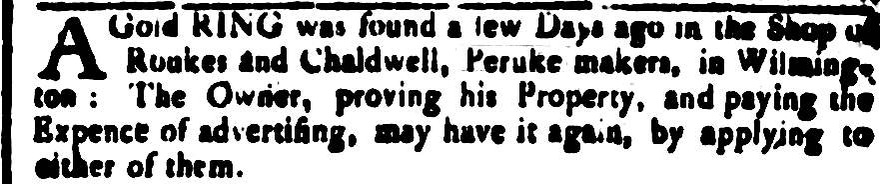

A newspaper ad placed by Roukes & Chaldwell, wigmakers in colonial Wilmington. (North Carolina Gazette, February 26, 1766)

6

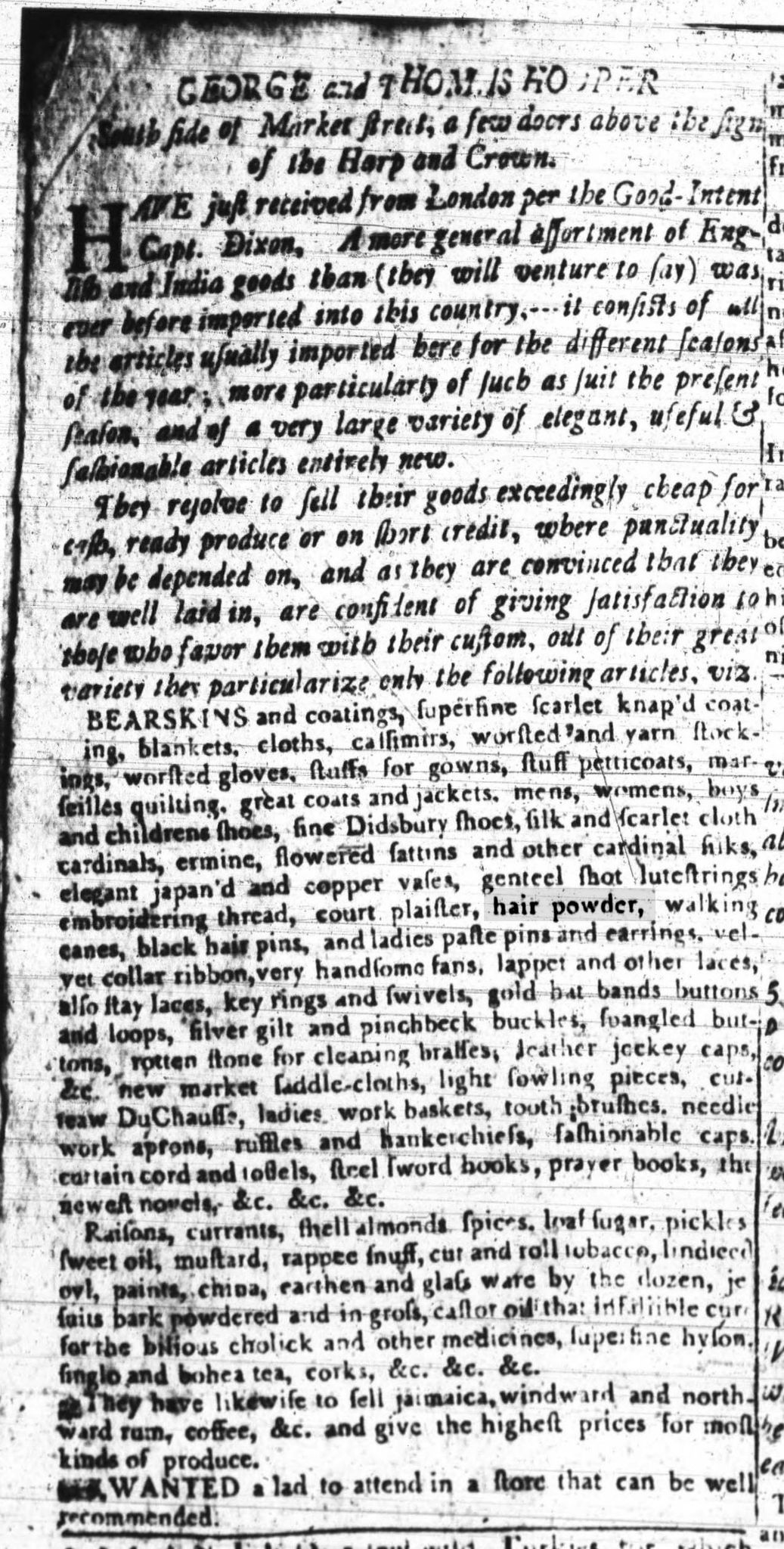

Wilmington merchants George and Thomas Hooper sold hair powder in their Market Street store. (Cape Fear Mercury, December 29, 1773). Their brother William Hooper was one of North Carolina’s three signers of the Declaration on Independence.

A Relic of the

Powdered Wig Era

in Old Wilmington

Quite often in the Public Archaeology Corps’ dig on Quince Alley in downtown Wilmington, we find an unusual and surprising artifact. And so it was with a piece, made of pipe clay, that turned out to be half of a wig curler. This artifact links us with the fashions and styles of colonial Wilmington, as well as the wider world of Europe and its American colonies.

King Louis XIV of France (reigned 1643-1715), whose court at Versailles set styles for aristocrats all over Europe, started wearing wigs when his own hair began thinning. The future Charles II of England, then living in exile in France after the English Civil War, helped popularize wigs in Britain when he was restored to the throne.

The French word for wig, perruque, was spelled “peruke” by the English. That was altered into “perwyck” and then to “periwig”, which was shortened into “wig”. Sometimes a peruke was a particular kind of wig, with long hair down the back and the sides, but colonial Americans used wig and peruke interchangeably.

Louis XIV-era wigs were usually made of human hair, and appeared in natural colors. By 1700, it became fashionable to coat them with white hair powder.

In the Thirteen Colonies, wigs were most often worn by upper-class or professional men. That said, some artisans and indentured servants wore wigs, and some aristocrats provided them for their slaves. American women were more likely to wear hair extensions instead of full wigs. Many men wore an artificial queue, resembling a pigtail that matched their own hair color. Most colonial Americans never bothered with wigs at all, or wore them only on special occasions.

Who did our wig curler fragment belong to? Some middle or upper-class households cleaned and maintained their own wigs, and owned numerous ceramic curlers. There were also shops that made and cleaned wigs.

Colonial Wilmington had a firm of “peruke makers” as early as 1766, according to an advertisement in the North Carolina Gazette. The peruke makers, the firm of Roukes and Chaldwell, occupied a building close to our dig site, on the northwest corner of Quince Alley and Front Street. The owners, John Roukes (also spelled “Rooks) and John Chaldwell (also spelled “Cholwell”) also obtained license to run an ordinary (tavern) in 1769.

Shops such as Roukes and Chaldwell’s sold ready-made as well as custom-made wigs. They measured the customer’s head, and picked out one of a selection of wooden blockheads that that was closest to the customer’s head size.

The finest perukes were made of human hair, which was strengthened with a small proportion of horse hair. Hairs were boiled, cleaned, and sorted by length, and then were woven together onto a base of silk threads. Wearers often shaved their heads or cut their own hair very short, to the wigs would stay on better.

Ceramic wig curlers were made of unglazed pipe clay. Some were simply straight rods, but most were rolled out to be larger at the ends and narrowed in the middle. Archaeologists often find them broken in half, as was our example. To curl the hair in a wig, it was wrapped around and clamped to the curler, then boiled for three hours or so. Then, the hair was dried and wrapped in brown paper and baked in an oven. Sometimes the paper-wrapped curls were packed in a pastry crust for added protection before baking. Old wigs were occasionally cleaned and curled with the same treatment.

Wigs fell out of favor after the mid-1700s, although professionals such as clergymen and physicians kept wearing them for some time. Lawyers and judges in Great Britain and the British Empire and the Commonwealth also kept on wearing their traditional wigs. They are still worn in criminal trials by barristers (lawyers who practice in open court) and judges in the UK today.

Hair powder remained in use after wigs faded from everyday life. Many men pulled their long hair back into a queue and covered it with powder so that it resembled a powdered wig. Made of wheat starch, powder often was tinted with pastel colors. 1780s records of Port Brunswick (a customs district covering the Cape Fear River region that was based in Wilmington) shows several shipments of hair powder for local merchants. Some hair powder came to Wilmington from the French colony of Haiti, or the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo, in the Caribbean.

The British Army required soldiers to grease and powder their hair. Each soldier used about one pound of hair powder every week. Powdering a wig or one’s own hair was a messy and troublesome chore. Hair was greased with pomatum, a sticky mixture of lard or suet tinged with cloves, orange oil, or other scents. Powder was sifted onto the hair, or blown on with a small bellows. A cone-shaped paper mask kept hair powder out of eyes and noses. To keep clothing clean, one wore a cloak that looked something like a modern barber’s cloth, or even a “powdering gown”.

An interesting reference to allergies came up at the October 1787 term of the New Hanover County Court: “Thomas Lamb, having it made it appear to the court that he could not bear the smell of hair-powder, flour, or wheat, it is ordered that he be exempted from attending as a juror …”

Europe and the early United States took their fashion cues from France. After the French Revolution began in 1789, French fashion was plainer and simpler than the fancy clothing and hairstyles of the despised regime of Louis XVI. The French stopped using hair powder, and a great many of the British and the Americans followed their lead. A British tax on hair powder, to pay for their war with Revolutionary France, also led many users to give it up.

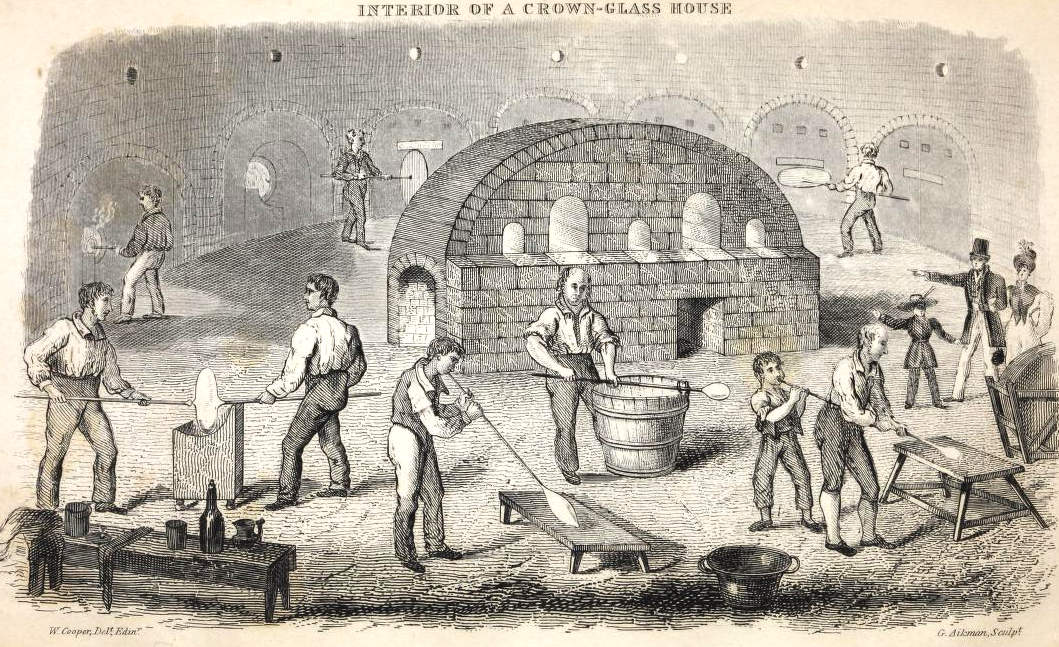

1

18th century window glass at St. Thomas’ Church (1734) in Bath, North Carolina.

2

Glass workers making crown glass. (William Cooper, The Crown Glass Cutter and Glazier’s Manual. Edinburgh, 1835.)

3

A glassmaker spun semi-molten crown glass into a flat “table” up to five feet wide. (“The Crown Glass Cutter”).

4

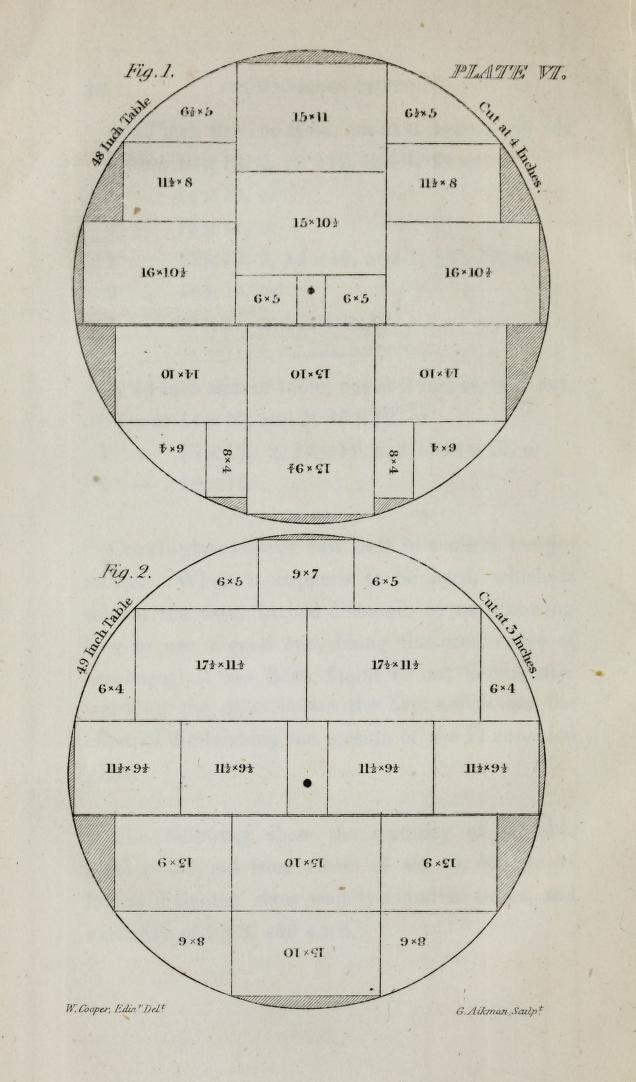

Patterns for efficiently cutting a table of crown glass. (“The Crown Glass Cutter”)

5

A “bull’s eye” from a pane of crown glass in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

6

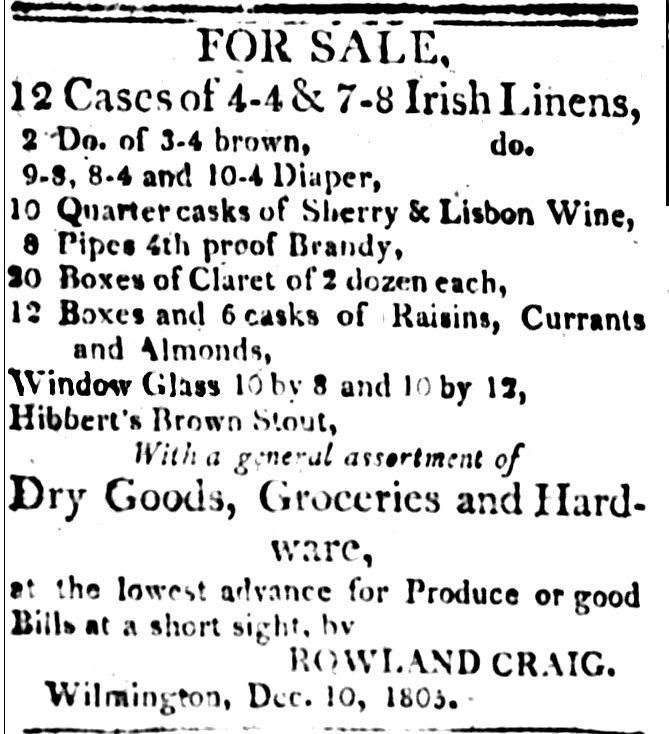

An ad mentioning window glass for sale in Wilmington. (Wilmington Gazette, December 10, 1805, from North Carolina Newspapers.)

A Look at the

Window Glass

in Quince Alley

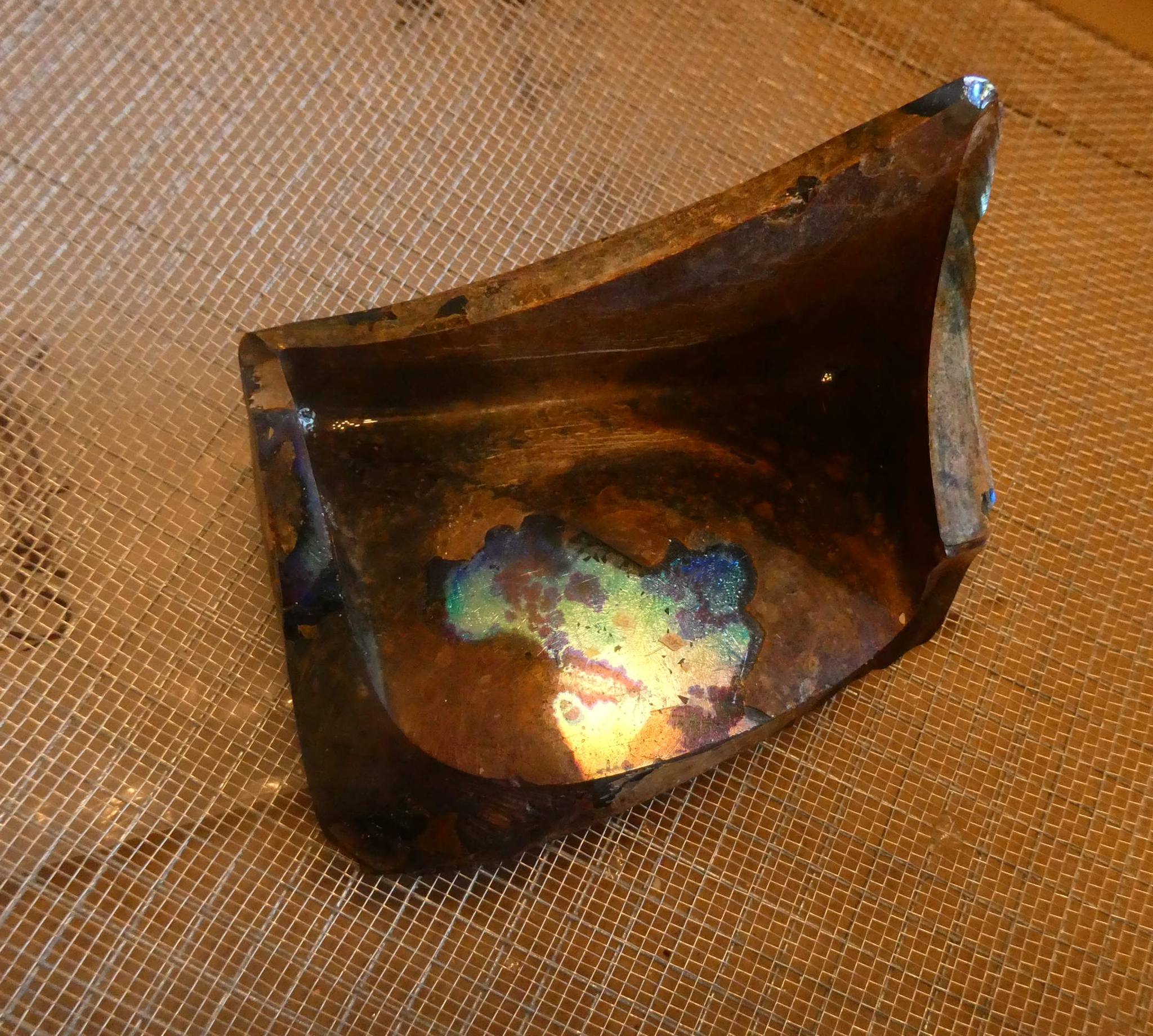

Our finds at the Public Archaeology Corps’ dig on Quince Alley in downtown Wilmington include a great variety of glass shards. Glass in the 18th and early 19th century was created by highly skilled glassmakers, who shaped molten glass by blowing air into it through long metal tubes, and rotating or spinning it. Besides fragments of hand-blown bottles, there is an abundant supply of shattered bits of flat glass from broken window panes. There were a few different methods of making window glass in the 18th century, but the finest quality and most popular type was created by the crown glass process.

An earlier method, broad sheet glass, was made by blowing a large glass bubble. Then, the ends were trimmed and the bubble cut and laid flat. Heated and crafted in a furnace, it would flatten out into acceptable window glass. Later in the 1700s, a variation called cylinder glass was developed, in which the glass was cut and shaped after being blown into a long cylindrical shape rather than a more rounded bubble.

A glassmaker started a sheet of crown glass by blowing a hollow ball or “crown” with the metal blowpipe. Then, a pontil (a solid metal tube) was attached to the crown and the pipe was removed. The glassmaker spun the pontil, and when necessary reheated the glass in a furnace to soften it. Spinning the pontil created enough centrifugal force to make the semi-molten glass spread out into a large, flat disk (called a “table”) as much as five feet across. When the glass cooled, it was cut into rectangular window panes, with the remaining scraps cut for other uses.

Crown glass was not perfect. Air bubbles, waves, and wobbles gave the glass “character” if not uniformity. Thickness varied somewhat from fine, thin glass in the outer areas of the disk, to gradually thicker glass toward the center. The very center formed a “bullseye”, with glass as much as one inch thick forming a circular blob in the middle, where the pontil was attached.

Today, bullseye panes are much prized for their distinctively quaint and archaic look. But, 18th century customers found little charm in the thick distorted bullseye panes, which let in less light and were impossible to see clearly through. Builders used some of them in out-of-the-way places such as windows for stables, or transom glass set high over a door. But, the bull’s eye panes were so hard to sell that many glassmakers just tossed them into the furnace to melt them down.

It required complicated math to get the most efficient use of a large circle of glass. Manuals for glassmakers included diagrams with precise measurements to get the largest number of large panes and the least waste.

The Port Brunswick Records (placed online by the North Carolina State Archives) list some shipments of window glass to Wilmington in the 1780s. From New York, on August 25, 1789 the sloop Millia brought for John Burgwin (the merchant who once owned the Burgwin-Wright House at Third and Market Streets in Wilmington) “2 Boxes Window Glass 10 x 12”.

On November 25, 1789, the schooner Wilmington Packet arrived from Charleston with a large cargo including, for merchant John Huske, “1 Box Window Glass – 10 by 12 – 100 ft.”. What is apparently the retail value (4 pounds; 7 shillings; and 8 pence) follows. At that price, the cost was about 10 ½ pence per foot.

Glass was not always cut into panes for shipment. Some crown glass was packed into crates as whole, half, or quarter tables, to be cut later as needed.

It was theoretically possible to mount a half or even a whole table of glass into a special window. Thomas Jefferson ordered several whole tables, about four feet in diameter, for Monticello. The glass was to fit in the oculus, a round window on the roof of his self-designed home. Every one of the great pieces of glass was broken in transit. Jefferson gave up and had a window of smaller panes made for the space. At last, in 1989, restoration crews working at Monticello lowered a hand-blown, 48-inch diameter crown glass table into the space at the top of the dome. Jefferson’s vision was accomplished about two centuries after he came up with the idea.

Usually in our dig when we find window glass, it’s in such tiny pieces that it’s difficult to tell which process was used. But, whether crown, broad sheet, or cylinder glass, the fragments are a reminder of the craftsmanship of skilled glassblowers, and the trade networks that brought their products by ship to Wilmington.

1

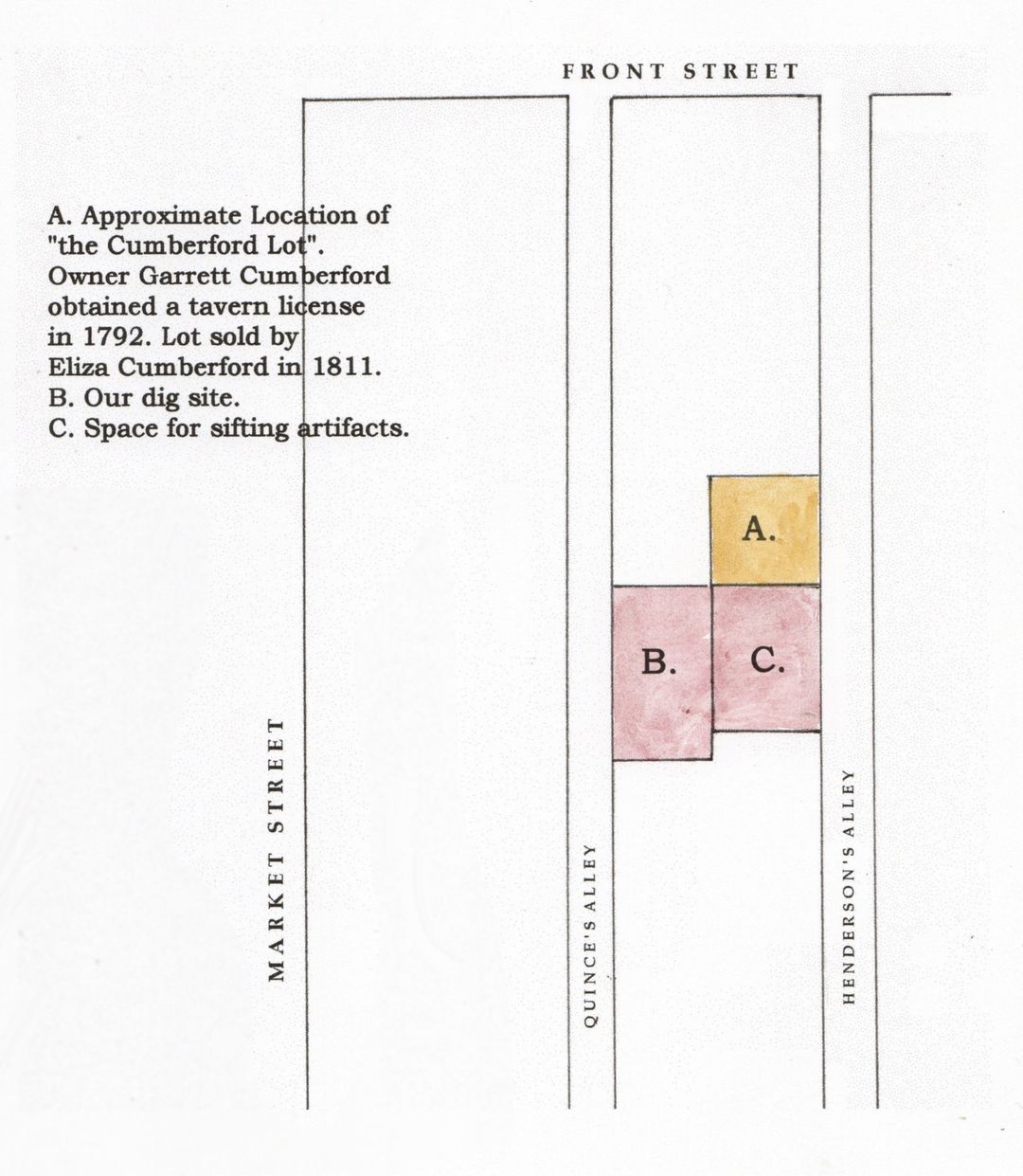

Approximate location of “the Cumberford Lot”, the probable site of a short-lived 1790s tavern.

2

Garret Cumberford’s estate inventory, 1793. It noted the house that stood on Henderson’s Alley near our dig site.

The Cumberford Lot

Henderson’s Alley was a popular spot for taverns and bars in Old Wilmington. Among the 18thand 19th century bar owners along the alley was Garret Cumberford, who received a tavern license from the New Hanover County Court on November 19, 1792. The only real estate in his name was a house and lot on the north side of Henderson’s Alley, purchased on May 1793 for £161. So it seems likely that he kept the tavern in his house. The tavern was in business for only a short time. Cumberford died later that year and his estate was handled in November 1793 by the county court. Much later, in March 1797, the county court appointed John Telfair as guardian of the Cumberford children.

Cumberford’s widow filed an inventory of her husband’s estate, including “one puncheon of Jamaica Spiritts Value Abt. £80” and a puncheon of “Northward Rum” valued at £45. A puncheon was a large barrel, holding 84 gallons. Northward rum was made in New England, rather than Jamaica and the other Caribbean islands.

There were also two tierces of rice and four barrels of flour; and one hundredweight of tobacco. (A hundredweight was 8 stone, or 112 pounds.) All of these goods of course had a place in a tavern selling food and drink.

Also in Cumberford’s estate were quantities of goods one might find in a small shop: 4 pieces of linen; 40 yards each of “Ozanbrigs” (osnaburg was a coarse fabric), flannel, and “checks”; one dozen stockings; “Shawls Jackett patterns & Callicoes”; and two pieces of muslin. There were also £3 worth of hardware and £2 worth of thread; “1 Rhem Writing paper & Earthenware”, worth £4; and £12 worth of “Bees Wax & Myrtlewax”. (A fragrant candle wax can be extracted from wax myrtles, small shrubs and trees that grow in our region.)

Cumberford’s house on Henderson’s Alley was valued at £200. He also owned a boat worth £50; £30 worth of household furniture; and carpenter’s tools valued at £10. The inventory was drawn up by Cumberford’s widow, who was not named.

Alas, the Cumberfords apparently left few other traces in the written records. No one else by the name of Cumberford renewed Garrett’s tavern license, indicating that this tavern closed after his death.

The property, which was for years afterward called “the Cumberford Lot”, was sold by “Eliza Cumberford of Chatham County” to John Larkins in 1811. We don’t know whether Eliza was the widow, daughter, or other relative of Garret Cumberford. Larkins paid $280 for the property, indicating that there was a house on it. It was almost certainly a fairly new house, as the area was devastated by fire in 1798. Deeds indicate that the lot measured 25 ½ feet along Henderson’s Alley and was 28 feet deep, including a 4 ½-foot easement in the alley. From comparing deeds of neighboring properties, we find that western edge of “the Cumberford Lot” came up against what is now the eastern wall of the roofless c.1850 brick warehouse ruins where we have our sifters set up for our excavation. So, long ago, the Cumberfords would have been the next-door neighbors of anyone who lived on our dig site.

1

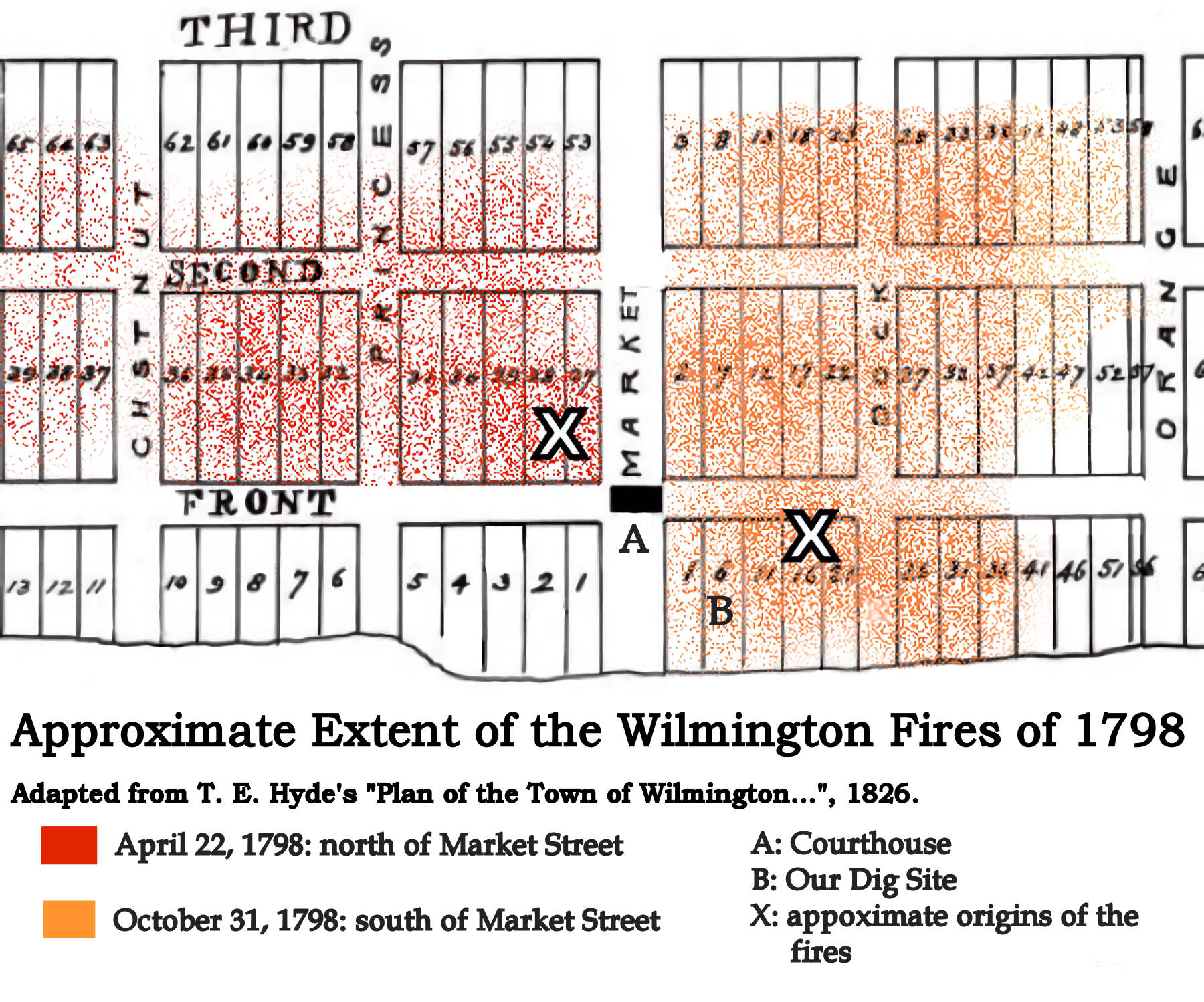

Approximate Extent of the Wilmington Fires of 1798.

2

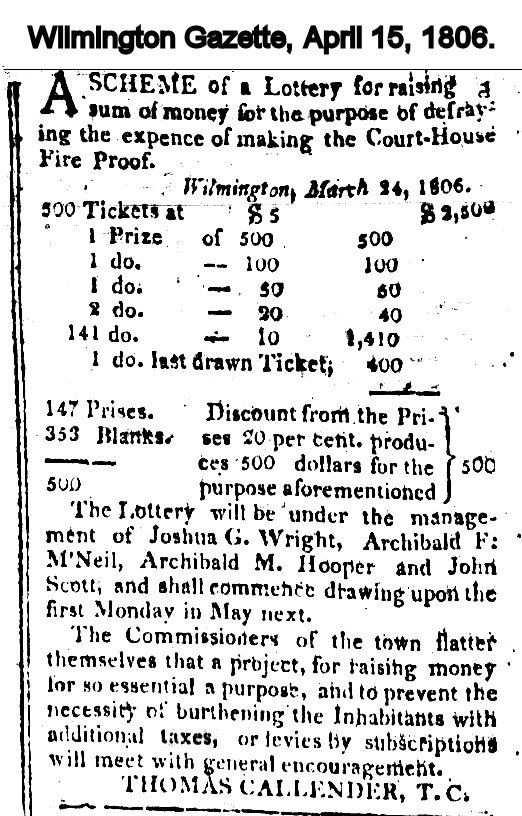

Wilmington Gazette, April 15, 1806

Two Major Fires in 1798 (to be continued)

Wilmington suffered two major fires in 1798. This map shows my best estimate of the affected areas, after sifting for information from newspaper items and deed records. Apparently each fire was confined to one side of Market Street. So, it was the October 31 fire that affected the site of our dig.

The county courthouse stood atop brick pillars, right in the middle of the intersection of Front and Market Streets. Frantic efforts saved the courthouse from destruction in either of the 1798 fires.

In 1806, a lottery was organized to finance the fireproofing of the courthouse. In the end, though, the courthouse was destroyed by a fire in 1840.

Archibald F. McNeill, one of the commissioners of the courthouse lottery, married Ann Quince. She was the daughter of John and Mary Quince, who once owned the land we’re digging in.

I’m working on a more detailed look at the fires of 1798, which will appear on the Public Archaeology Corps web site soon.

1

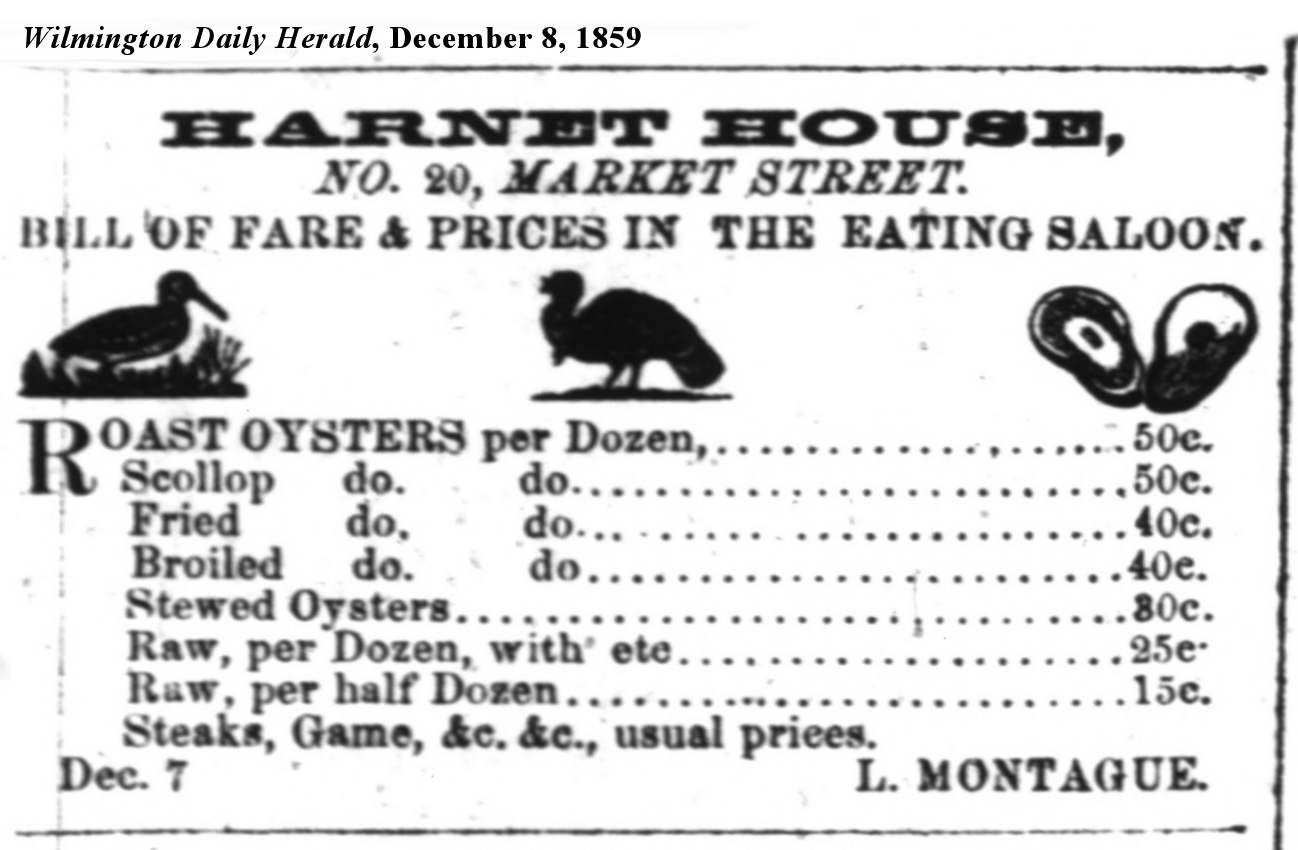

Wilmington Daily Herald, December 8, 1859

2

Advertisement for Oysters

The Oysters of Quince’s Alley

Quince’s Alley near Front Street has turned up oyster shells. We know that Isaac Belden opened an oyster house on Quince’s Alley in 1842. Belden stayed in business there until the Wilmington fire of 1845, which destroyed nearly the whole block. It’s also known that James Jennett ran a tavern on Quince’s Alley in the 1790s. Jennett and any earlier tavern owners might well have also served oysters that we found a couple of centuries or so later.

Isaac Belden had quite a bit of competition in the oyster business. Oysters were sold at Brigg’s Carolina Coffee House on Front Street. Daniel Miller’s bar room also sold oysters. Miller’s bar was just a stone’s throw away from Belden, being located on Henderson’s Alley just a bit closer to the river than our dig site. Miller had closed up shop by 1844, as a newspaper ad offered his old place for rent.

S. Ghio’s tobacco and fruit shop, which opened in 1844, sold pickled oysters from the James River in Virginia. By 1845, the firm of Foster & Tilly advertised oysters that came by train from Norfolk, Virginia.

Belden advertised in 1843 that he had oysters “fresh from the Upper Sound every day”, which he sold for 18 ¾ cents a plate. If you followed Market Street out of town, you’d soon be on the old main road that more or less followed the route of modern U.S. 17, getting within a couple of miles or so from the sounds behind Wrightsville Beach, Figure Eight Island, and Topsail Island. Oysters can live for days out of the water, so they’d easily survive a cart trip down to Wilmington.

All North Carolina (and East Coast) oysters are of one species, Crassostrea virginica, or the Eastern Oyster. That said, there is great variation in the Eastern Oyster, depending on the depth, salinity, and other variations of the waters they grow in.

The shallow sounds of New Hanover County had many places where one could find “raccoon oysters”. They were notably smaller than those dredged (with more difficult labor) in deeper waters. Raccoons were able to head out at low tide to get these little oysters, hence their name. In 1916 the Morning Star explained that raccoon oysters “cannot be shipped to outside points profitably, as they are very hard to open unless steamed or roasted. It is estimated that the ordinary oyster opener in the larger cities could open three Norfolk oysters while he was opening one of the ‘Raccoon’ variety.”

Judging by prices, Wilmingtonians preferred oysters from beyond New Hanover County’s waters. For instance, the price in April 1876 was $2 for a bushel of New River oysters from Onslow County, and 75 cents for a bushel of oysters from Myrtle Grove Sound.

Many of Wilmington’s saloons and hotel dining rooms offered fresh oysters along with their selections of liquor, wine, and beer. In 1859, the Harnet House on Market Street sold oysters roasted, “scollop” (baked with bread or cracker crumbs, butter, cream, and various other ingredients), fried, broiled, or stewed.

Oysters were most flavorful in the cooler months, giving rise to the custom of eating them only “in months with an ‘r’”; that is, from September to April. Belden’s first newspaper ads for his oyster house came in November 1842, and continued until May 10, 1843. On June 7, Belden advertised a new business for the warm season: a “bathing house where cold and warm baths can be had at all hours between sunrise and ten o’clock at night”. From that time on, Belden’s ads only mentioned the bathing house. His last advertisement appeared on September 5, 1845.

The final mention of Belden’s business was in a list of buildings lost in the great Wilmington fire of November 4, 1845. The fire broke out in Henderson’s Alley, “in a small shed-like wooden building, attached to a larger wooden building which had been formerly used as a bar-room, but for some weeks had not been occupied”. Quite possibly, this was Dan Miller’s old bar room.

Belden appeared on the list of business owners affected by the fire as “Isaac Belden – oyster house”. The same fire also destroyed the premises of two other known sellers of oysters in town: S. Ghio, and Foster & Tilley.

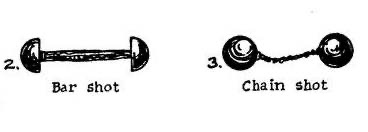

1

Bar shot and chain shot. Albert Mauncy, Artillery through the Ages: A Short Illustrated History of Cannon, Emphasizing Types used in America. (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1949), p. 64.

2

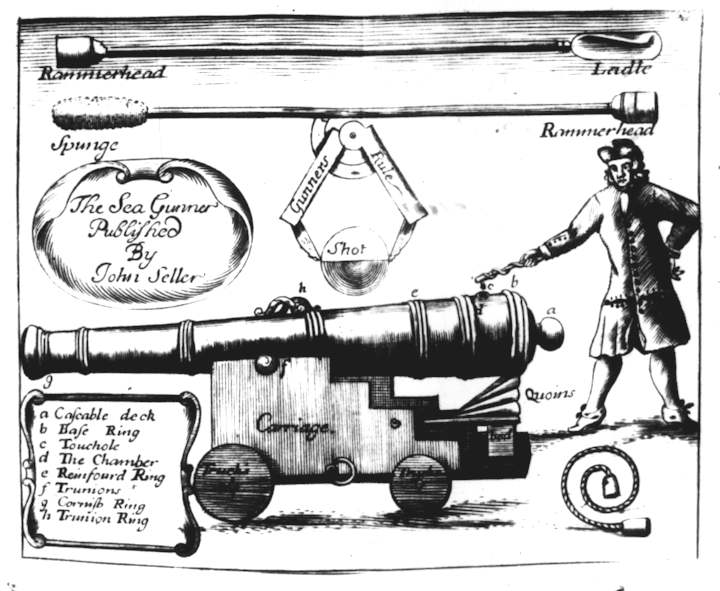

Bar shot was fired from standard cannons. John Seller, The Sea-Gunner Shewing the Practical Part of Gunnery as it is Used at Sea (London: 1691).

3

“Our” bar shot, found near Quince’s Alley.

4

Douglas Dickinson working on the bar shot in our lab.

The Bar Shot from Quince’s Alley

Doug posted a couple of days ago about cleaning one of our most interesting finds, the bar shot, to prepare it for preservation. Found in the Public Archaeology Corps’ dig on Quince’s Alley in downtown Wilmington, the piece of bar shot ties Wilmington’s history as a port with the sailing navies and privateers of the 18thcentury.

Used on warships, privateers, pirate ships, and armed merchant vessels, bar shot came in various forms. Each kind, though, had two solid-shot cannon balls or iron projectiles, linked by a bar of iron. Fired from a ship’s regular cannons, a bar shot spun around during its flight, and was intended to cut the rigging, sails, or masts of an enemy vessel.

There were as many as four kinds of bar shot, in addition to “chain shot”, which linked two cannon balls with a length of chain. One style used in the 1700s was made of two round cannon balls connected by a bar in the middle, rather resembling a barbell. Another style (“half-round shot”) resembled a cannon ball sawn in two, and fastened to each end of an iron bar. Sliding bar shot was held together by long telescoping iron bars; when fired, the bars expanded to make a projectile almost three feet long.

There was another style, known as “hammer shot”, which most resembles the one we found here near Quince’s Alley. Hammer shot was made with two short cylindrical iron pieces connected by the iron bar.

Numerous fragments of various kinds of bar shot have been recovered from the Queen Anne’s Revenge, the pirate vessel scuttled by Blackbeard in Beaufort Inlet in 1718. Pirates and privateers found bar shot especially useful. They might force a prize to surrender by cutting down its masts and rigging, but without damaging the hull and sinking the vessel and its cargo.

Numerous pieces of bar shot, evidently fired from British ships during the Revolutionary War, have been found in New York. Some of that bar shot, found in archaeological sites, seems to have been re-used as andirons or “fire dogs” in campsites or in soldiers’ huts.

Precisely measuring our piece of bar shot is tricky, because of the corrosion of the iron, but our piece evidently could have fit into a cannon barrel with a bore of a bit less than 3 ¼ inches. In 1764, the Board of Ordnance in Great Britain compiled a list of standard cannons by size. An iron 4-pounder gun had a bore of 3.21 inches – just about right for our bar shot.

Four-pounder guns were used by the Royal Navy in the Cape Fear during the Revolution. British frigates and sloops of war drew too much water to get as far up the Cape Fear River as Wilmington. Instead, three shallow-draft row galleys, the Adder; the Comet; and the Dependencewere stationed off Wilmington and in the Cape Fear and Northeast Cape Fear Rivers. The latter was once the Continental galley Independence; the British captured the galley and changed its name. British records indicate that the Dependencecarried six 4-pounder guns plus a much larger 24-pounder.

So, where did our bar shot come from? There are quite a few possibilities. Besides the Royal Navy operating in the Cape Fear, several privateer vessels sailed into or out of Wilmington between the 1740s and the War of 1812. Even merchant vessels carried cannons until after the War of 1812, and the final suppression of piracy in the Western Hemisphere in the 1820s. And, there are examples of bar shot in museums in England that were saved as mementoes after being fired into British warships. However our bar shot ended up in Quince’s Alley, it’s a great link to Wilmington’s maritime past.

1

Close-ups of the Georgian-era pipe bowl.

2

Close-ups of the Georgian-era pipe bowl.

3

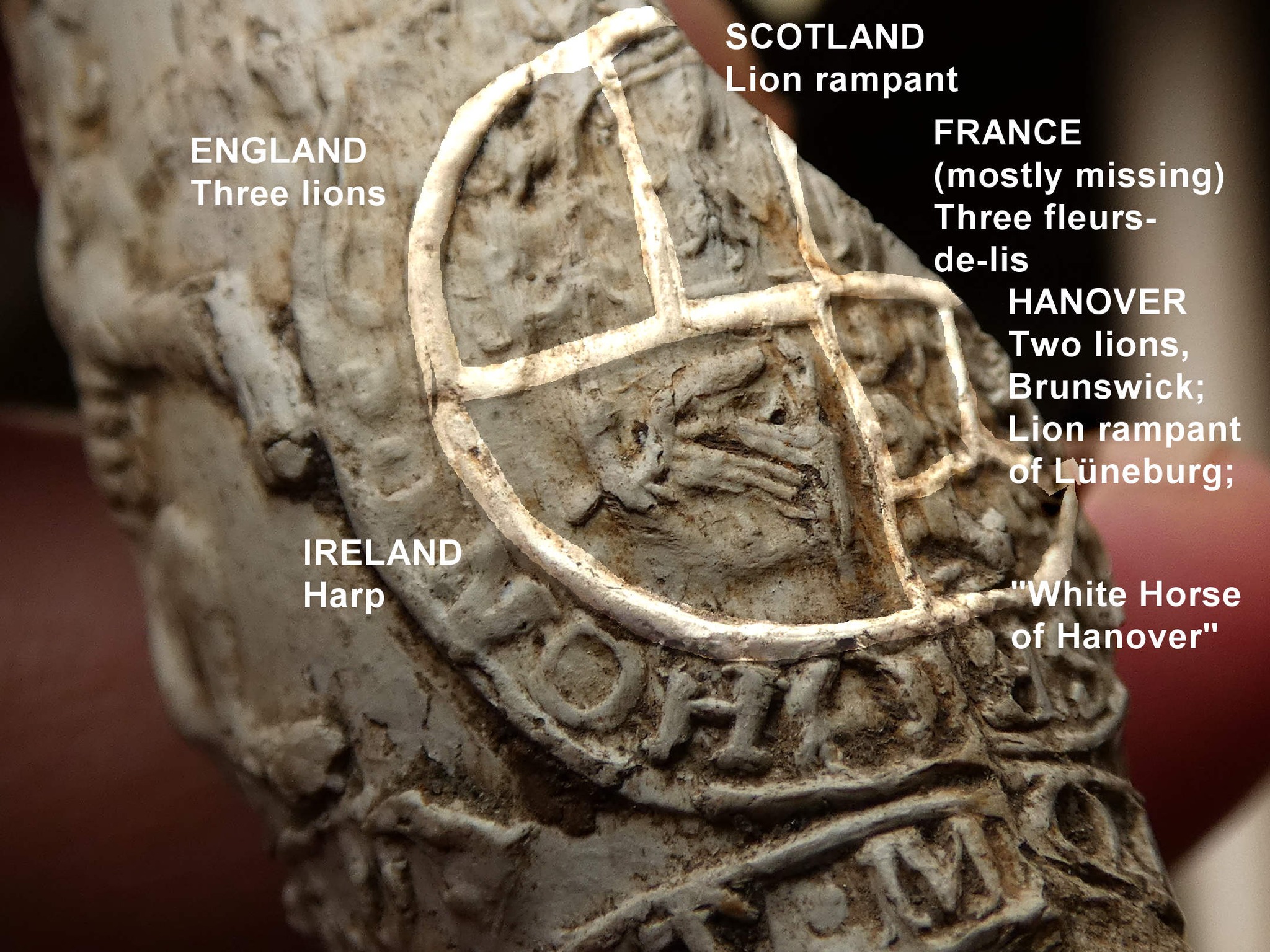

Key to heraldic symbols

4

The Hanoverian symbols: two lions for Brunswick; one lion rampant for Luneburg; and the “White Horse of Hanover”.

5

An English lion supports the shield.

6

A color version of the Georgian-era coat of arms, at Tryon Palace in New Bern.

7

The coat of arms on the North Carolina Gazette, printed in Wilmington in 1766.

8

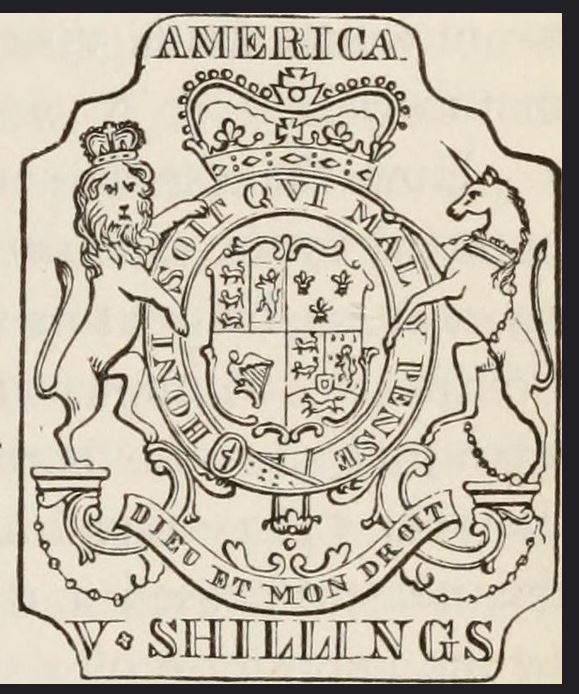

A simplified version of the coat of arms, on one of the Stamp Act-era tax stamps.

9

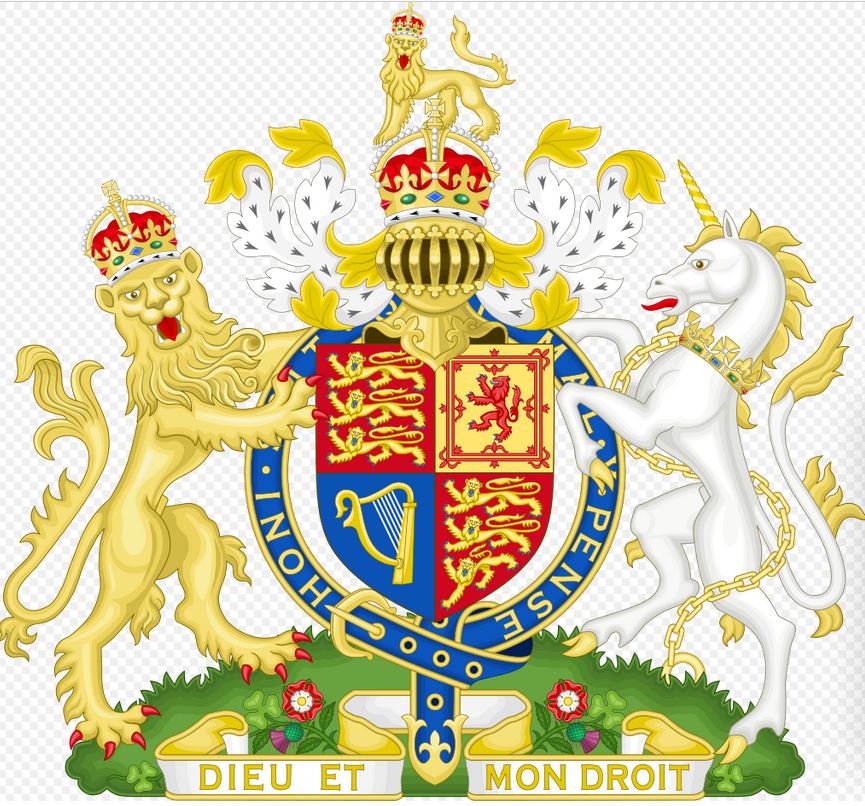

The modern-day royal coat of arms shows several changes since the mid-1700s. (Wikipedia Commons).

King George’s Tobacco Pipe Bowl

Among the picturesque echoes of England and Europe found in the Public Archaeology Corps’ downtown Wilmington dig are objects decorated with coats of arms. Each coat of arms is a unique heraldic symbol, made from varying combinations of traditional elements. In the Middle Ages, unique colors and symbols emblazoned on shields helped distinguish one knight from another on the battlefield or in a tournament. Long after armor-clad knights were a thing of the past, coats of arms were still passed down by inheritance as symbols of families, including the royal family of Great Britain.

Perhaps the showiest coat of arms we’ve found was on a clay tobacco pipe bowl fragment, showing the royal coat of arms of Great Britain. Although the upper right portion of the coat of arms is missing, it’s clearly a version used by the Hanoverian kings of Great Britain during the 1700s.

The German state of Hanover began a long association with Great Britain after the death of Queen Anne in 1714. The last of the House of Stuart monarchs, Queen Anne left no surviving children. Stuart cousins with claims to the throne were plentiful, except for one problem: British law required a Protestant monarch. Those relatives closest to Queen Anne were all Catholics. So, the British throne went to the first Protestant claimant. No. 58 in line was George Ludwig, the Elector of Hanover (so-called because the ruler of Hanover was one of the royals who elected the Holy Roman Emperor). As King George I of Great Britain, the new king and his descendants were also the rulers of Hanover for more than a century.

Like many royal coats of arms, the shield or escutcheon (the central part) is quartered. The four quarters were crowded with symbols of the history of the Georgian-era monarchy.

The upper left quadrant was halved. On the left side were three lions passant guardant (passant means the lion is walking toward the left, with the right forepaw raised; guardant means the lion is shown sideways but with his head turned to look at the viewer). The three lions represent England. The right half of the quadrant showed the lion rampant (standing with its forepaws raised) of Scotland.

The now-missing upper right quadrant would have showed three fleurs-de-lis. These stylized lily flowers, symbols of France, reflect centuries of entwined history and conflict after the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. William the Conqueror and generations of his French-speaking successors ruled England and a collection of French lands. Eventually the English kings lost their possessions on the Continent, but the fleur-de-lis remained on their coats of arms reflecting their claims to the French throne.

The lower left quadrant shows a harp, which for centuries has been a symbol of Ireland. Today, the harp represents Northern Ireland on the current royal coat of arms, while the Republic of Ireland shows the harp on its coins and passports.

Symbols of the new king’s German roots filled the rather busy lower right quadrant. The “White Horse of Hanover” appears on the lower portion. The upper portion represented other possessions of the ruler of Hanover. Two lions passant guardant, in the upper left, symbolized the Duchy of Brunswick. On the upper right, a lion rampant stood for the Duchy of Luneburg.

A full version of the Hanoverian British coat of arms also included a tiny crown in the center of the lower right quadrant, representing the Holy Roman Empire. (I must confess to being unable to see this tiny detail, if it’s even present on our little pipe bowl.)

Further heraldic elements surround the escutcheon or shield. It is supported by an English lion on the left. If our pipe bowl wasn’t broken, there would be a unicorn representing Scotland on the right.

Around the shield appears an inscription in Norman French, (“Evil to him who evil thinks”). This is the motto of the Order of the Garter, an order of chivalry founded by King Edward III in 1348.

Below the shield is another French motto, Dieu et Mon Droit(“God and my right”). Seen as a statement regarding the divine right to rule, this dated back to the time when Richard I (a.k.a. “Richard the Lion-Heart”) shouted it as a battle cry in 1198.

The royal coats of arms went through several changes after the American Revolution. After 1802, with the signing of the Treaty of Amiens, the fleurs-de-lis disappeared when the British finally dropped their claim to the French throne.

Hanoverian symbols disappeared after 1837, with the accession of the 19-year-old Queen Victoria. Hanoverian law forbade a woman to inherit the crown, so the British-Hanoverian ties were severed. Victoria’s uncle, Ernest Augustus, the Duke of Cumberland (and a son of King George III) was chosen as the new King of Hanover.

Carving the mold for this clay tobacco pipe must have been quite a challenge. Yet, the unknown carver succeeded admirably in the task of squeezing centuries of British royal history and heraldry into a tiny space.

1

2

3

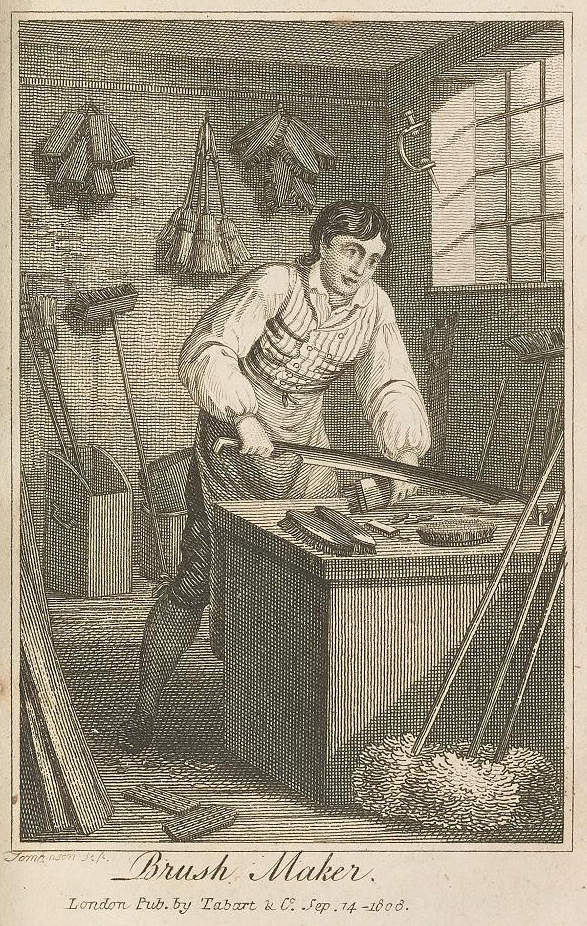

Brushmaker at work.

4

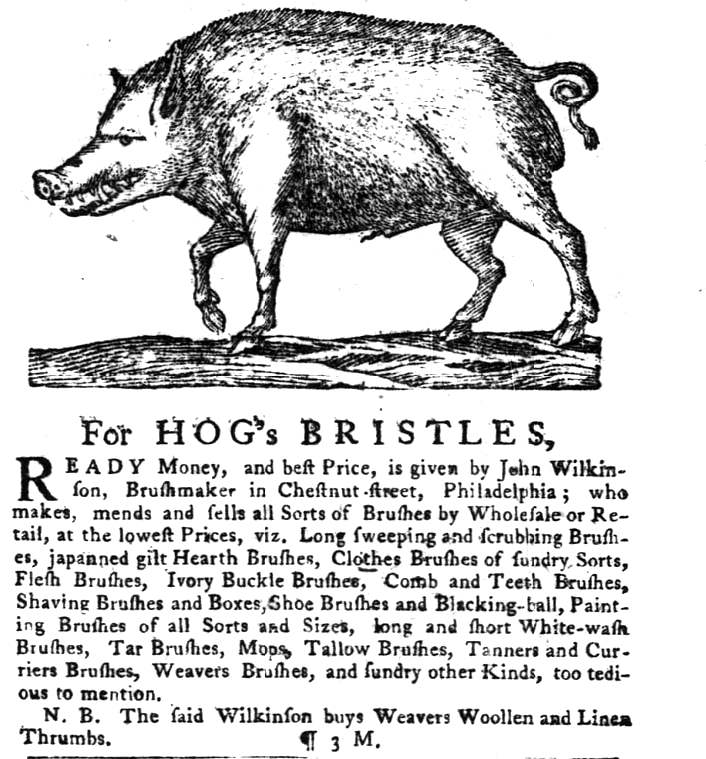

Brushmaker’s ad. (Pennsylvania Gazette, March 4, 1762.)

5

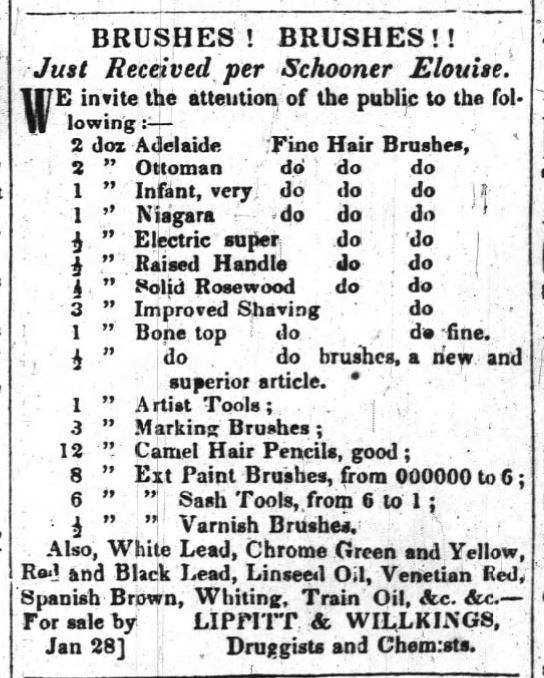

A great variety of brushes, for sale in a Wilmington drug store, 1848. (Wilmington Journal, January 28, 1848.)

6

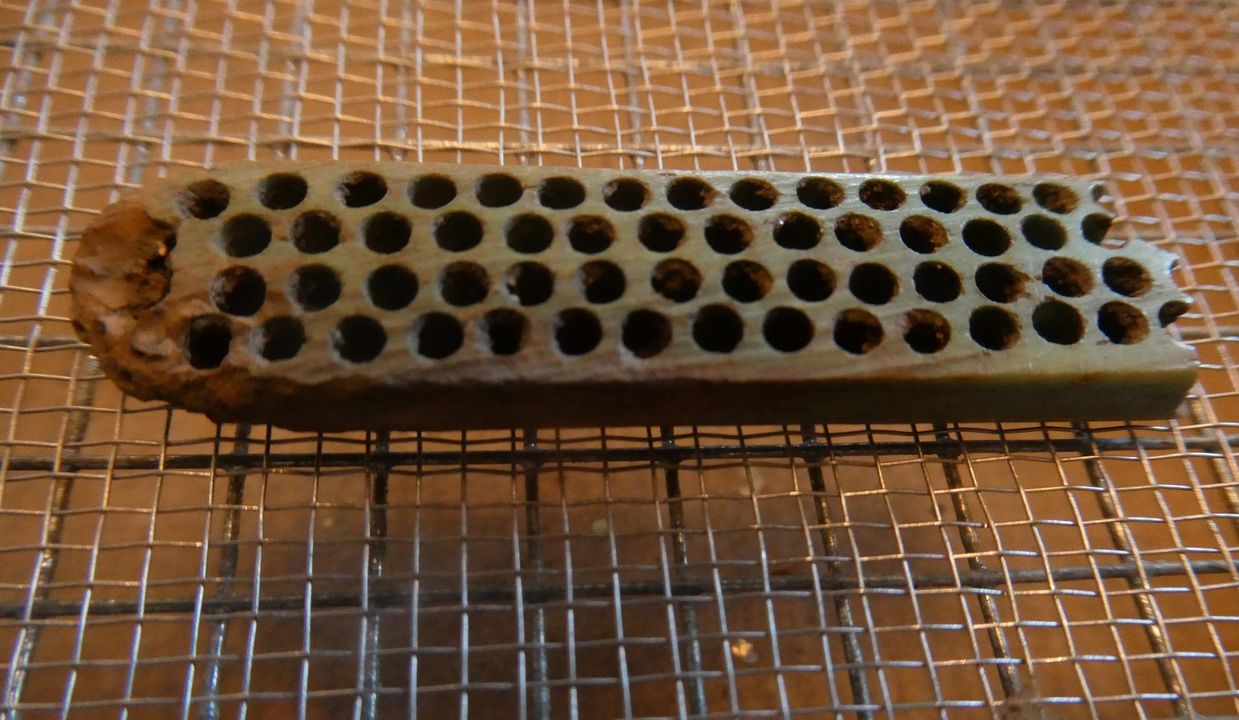

Part of a bone handle toothbrush, found by PAC in Quince Alley.

7

Part of a bone handle toothbrush, found by PAC in Quince Alley.

Brushes with Bone Handles from Quince’s Alley

We’ve found several pieces of toothbrushes and combs made of animal bone at the Quince Alley dig, and recently, a larger hand-shaped and drilled bone brush turned up in the Public Archaeology Corps Lab.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the same artisans made many types of brushes. John Hanna of Philadelphia advertised in the Pennsylvania Gazette in 1768 that he made “all sorts of brushes, mostly of English hair, and common brushes of this country hair … He has now got a large and neat assortment of sweeping, scrubbing, hearth and white-wash brushes; best mahogany, and three different sizes of painted clothes brushes; weavers, tanners, hatters, painters and furniture brushes; shoe and kitchen hearth brushes, &c., &c. …” Hanna guaranteed “that if the bristles come out in any reasonable time, with fair usage, he will give new ones for nothing. … He has of late stamped his name on his brushes, so that if they should fail, people may know where to bring them to be exchanged.”

Hog bristles were used for anything from artists’ brushes to toothbrushes and scrubbing brushes. Bristles from the back and shoulders of hogs were laboriously selected and sorted. The best quality was thought to come from hogs raised in cold climates. Most hog bristles for brushes were imported from Russia and Germany, and later, from China.

Some English and American brush makers offered ready money for hog bristles. In 1792, Cooper’s Trunk and Brush Manufactory in New York offered two shillings a pound for hog bristles, if they “were well cleaned and free of filth”. Gathering and cleaning hog bristles was so time-consuming that local production was minimal, and most American and English brushmakers relied on imported bristles.

18th century records of Port Brunswick (a customs district including Brunswick Town and Wilmington) note a few incoming shipments of brushes. 22 dozen brushes arrived in 1774, aboard the ship Commerce, from Bristol, Great Britain. In 1788 and 1789, small shipments of brushes arrived in vessels departing from Grenada, and New Providence in the Bahamas.

Wilmington’s newspapers seem to mention nothing about locally made brushes, but ads mention brushes made in the Northern states. For instance, in 1816, R.W. Brown advertised brushes and brooms made at the New York State Prison. In 1830, G. W. Davis “returned from the North” with a vast array of merchandise, including “Scrubbing, Hair, Shaving, Cloth, Dusting and Show Brushes, Hearth Brushes and … White Wash Brushes …”

Brush handles were made from wood as well as ox or cow bones, and some fancy brush handles were made of ivory or silver. Bones intended for brush handles (or “stocks”) were washed, bleached, and cured before being cut and shaped. In 1900, William Kiddier wrote in The Brushmaker, and the Secrets of His Craft and Romance, that the carved bone handles were polished by a long period of being tumbled in a barrel filled with whiting (powdered calcium carbonate).

Holes were drilled into the stock. By using a template, the holes could be spaced evenly. In bone brushes, the holes did not go quite all the way through. On the back, the brushmaker scored shallow lines with a cutting or graving tool, just deep enough create a channel connecting the holes. There was one such line for each row of bristles.

At a brushmaker’s establishment, a “hair hand” carefully cleaned the bristles, and sorted them by length and thickness. Bristles were made into small bundles, tied around the middle with wire or thread, and then doubled over. The bundles were then pulled into the holes in the stock. Then, the wires or threads holding each bundle were pulled through the holes; tied into knots to hold them in place; and further held fast by various adhesives. Afterward, the channels or grooves on the back of the handles were filled with substances such as wax to smooth them out. This would also hide the knots holding the bristles in place. To finish the brush, the ends of the bristle bundles were trimmed to make them even.

Although hog bristles were a common component of brushes, other materials were also used. Finely split whalebone was once widely used for bristles. Toothbrushes were also made with horse hair and badger hair. Synthetic fibers such as nylon began coming into use for brushes just before World War II.

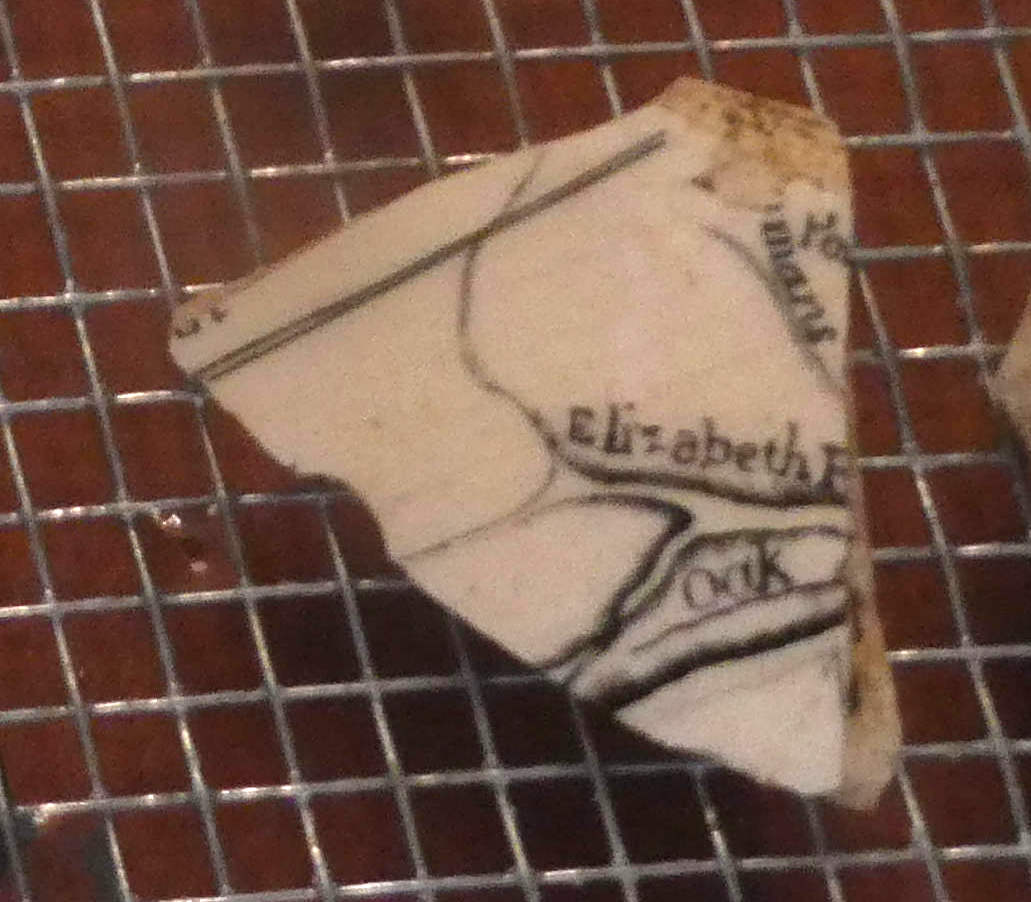

1

Wilmington, on one of our transferware map fragments.

2

A piece showing Oak Island and the surrounding areas.

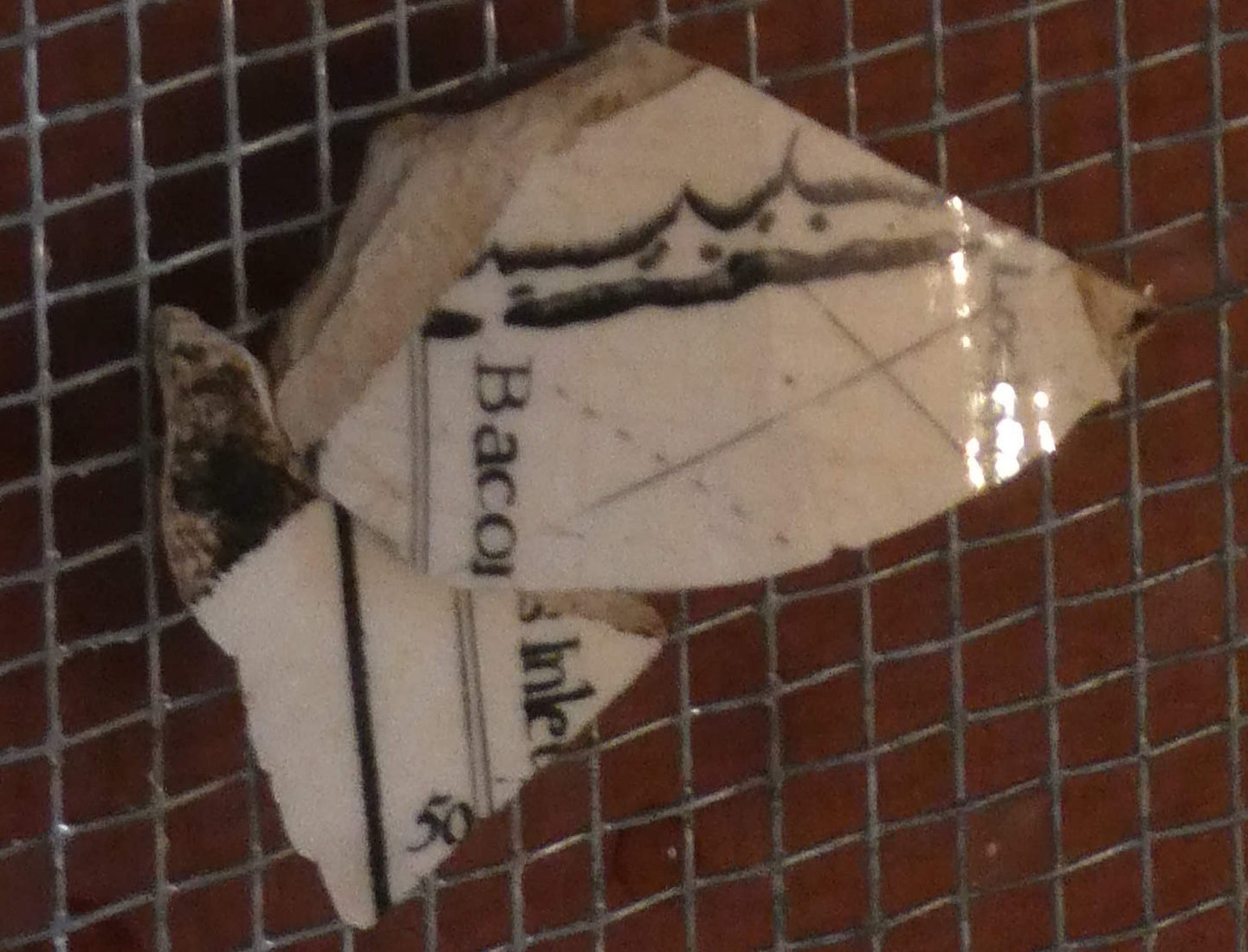

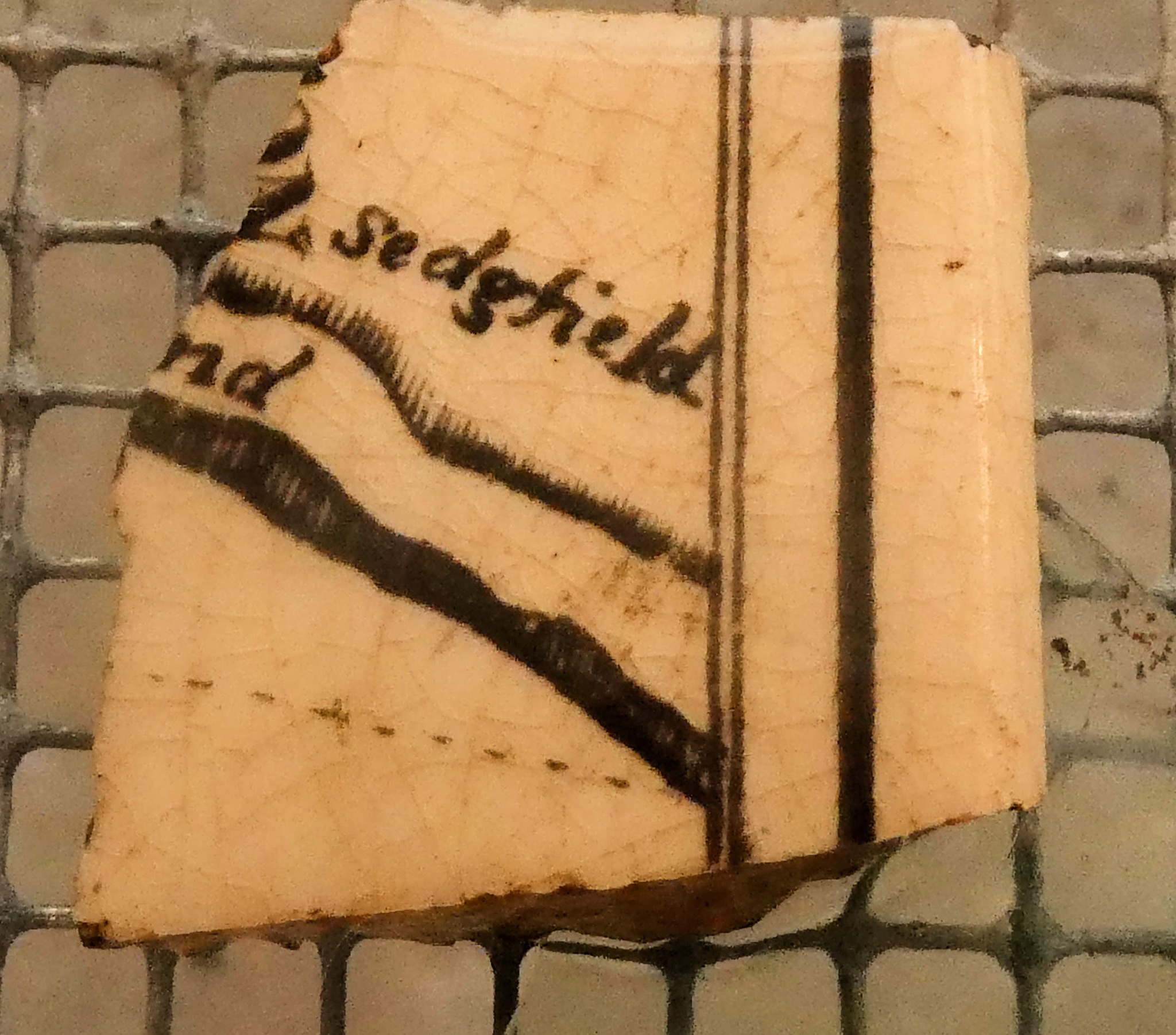

3

Pieces showing Bacon’s Inlet on the Brunswick County coast.

4

Pieces showing Bacon’s Inlet on the Brunswick County coast.

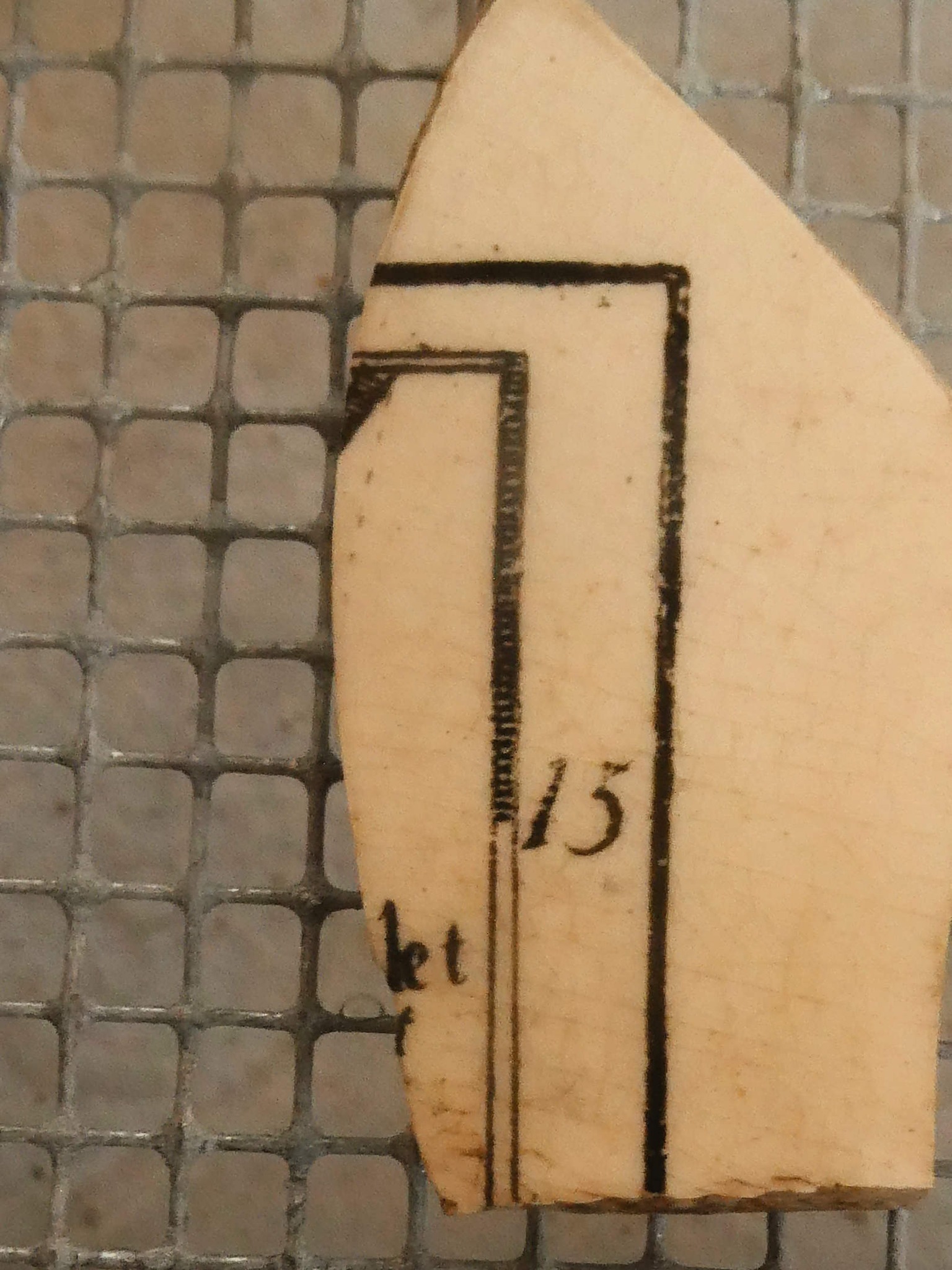

5

Latitude markings.

6

Latitude markings.

7

8

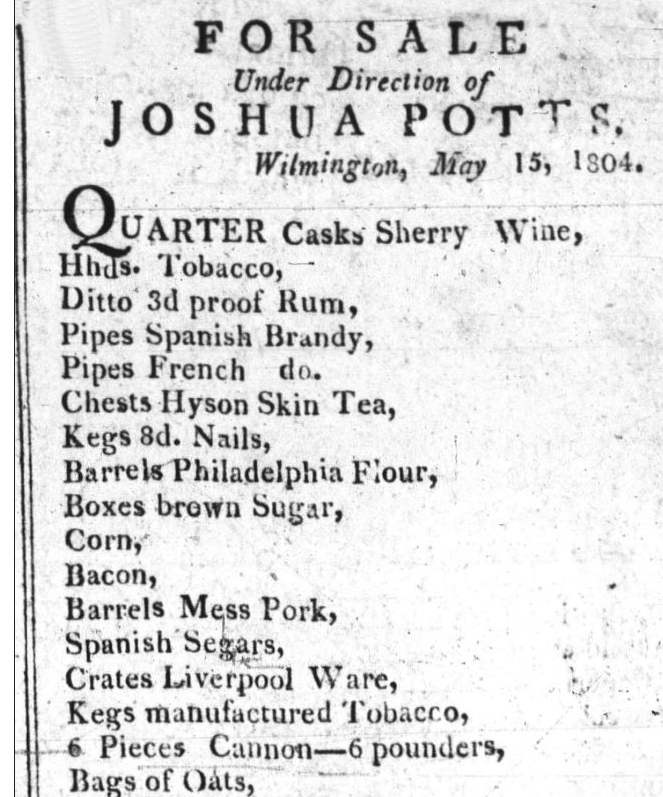

Joshua Potts’ Wilmington Gazette ad, offering Liverpool ware and 6-pounder cannons.

9

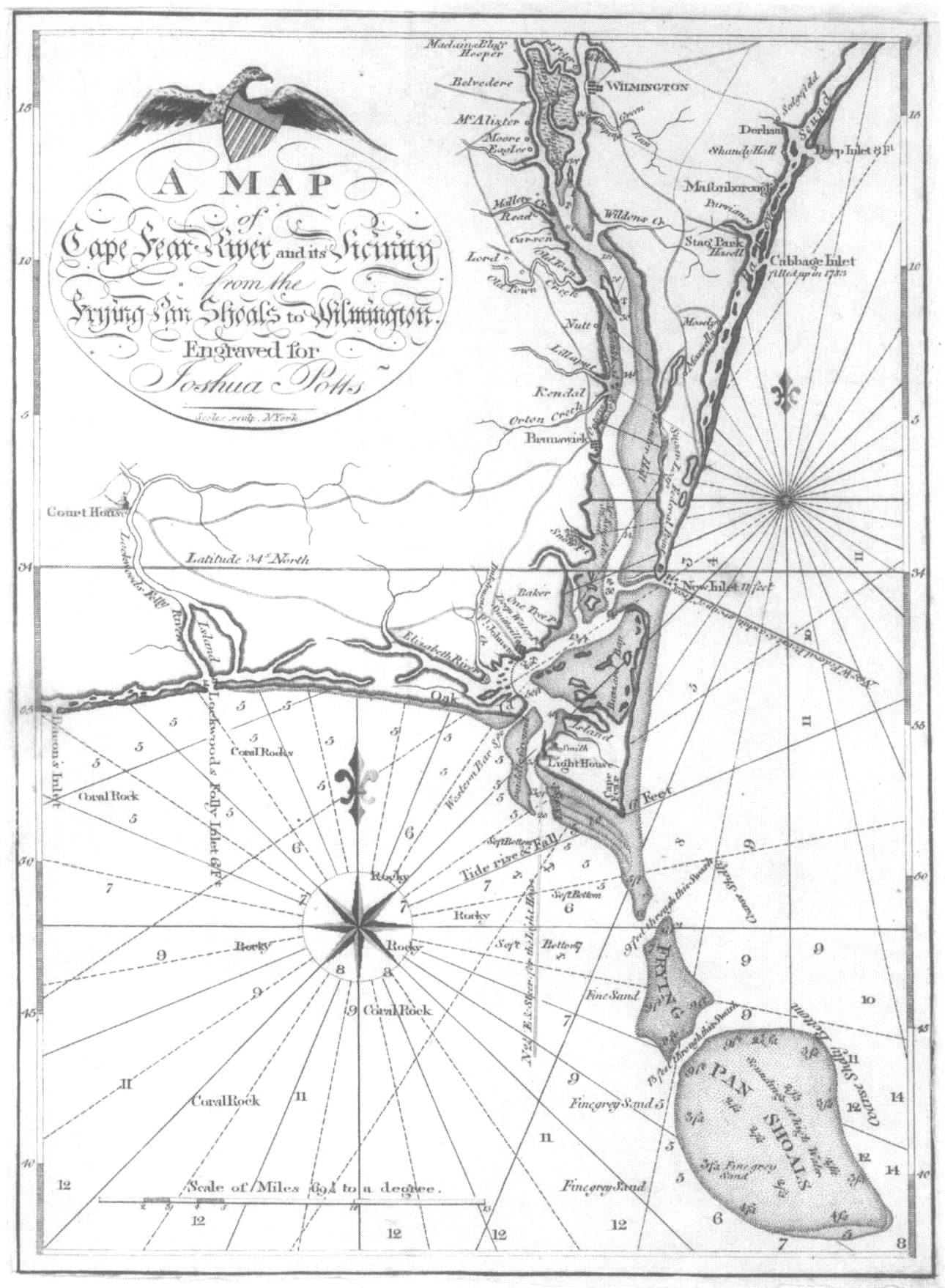

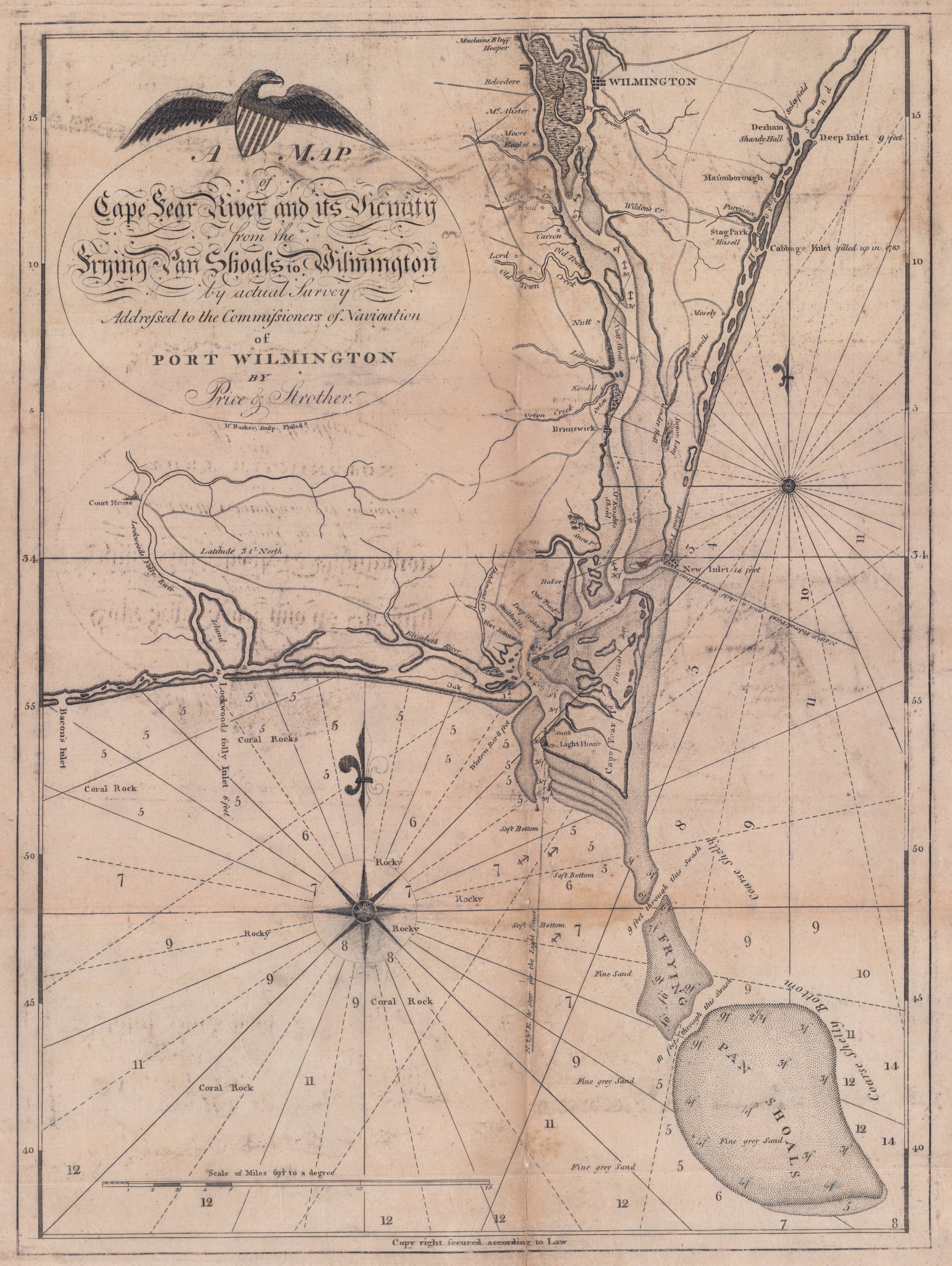

The Price-Strother Map of the Lower Cape Fear region, c. 1798. (North Carolina Maps).

9a

Joshua Potts’ commissioned copy of the Price-Strother Map. (Goree, John A. “Price and Strother, Joshua Potts, and the Evolution of ‘A Map of Cape Fear River and Its Vicinity’”. North Carolina Historical Review 76, no.4 (October 1999).

Black Transferware Map Fragments

One of the most picturesque artifact collections uncovered in Quince Alley by the Public Archaeology Corps is a handful of black transfer ware ceramic bits. They are pieces of a map of Wilmington and the Lower Cape Fear region at the turn of the 19th century.

Details on the ceramics echo two maps of the Lower Cape Fear region, dating from the turn of the 19th century. In 1798, Jonathan Price and John Strother issued a large chart covering the Atlantic Coast from Cape Henry, Virginia to Cape Romain, South Carolina. They also issued another chart measuring 13 7/8 by 18 3/4 inches, which showed in accurate detail the Cape Fear River from Wilmington to the Atlantic and the surrounding coast and countryside.

A smaller version of the Price-Strother chart of the Cape Fear (5 3/4 by 8 inches), with less detail, was ordered by Wilmington merchant Joshua Potts. He hired John Scoles of New York to engrave the plate for his map. Although rather obviously based on the Price-Strother chart, there is no mention of their names on Potts’ version.

Joshua Potts (c. 1751-1825) was a Wilmington commission merchant, surveyor, and lawyer who had served in the state legislature. In 1792, he also became one of the founders of Smithville (now Southport). He had a small copy of the Price-Strother chart made about 1803. Potts wrote Gov. William Hawkins of North Carolina in 1813, “I had many of them struck which I used to send with Wilmington Prices, to Correspondents at distant and Foreign Ports”.

Ceramic map pieces with readable text recovered from Quince Alley show many local places. Wilmington appears as a little cluster of a dozen dots. This appropriate enough for a town that may have had a dozen full blocks at the time. The Wilmington fragment also shows a bit of Eagles Island. A tiny bit of broken text at the bottom might indicate a spot just south of Wilmington that was marked “Green” on the Price-Strother and Potts maps. In the mid-1700s Dr. Samuel Green established a plantation south of Wilmington that was called Greenfield. Green had a mill on his land, and the body of water backed up by the dam is the centerpiece of the city’s Greenfield Park now.

North of Wilmington on our map fragment was Hilton and a tiny bit of Smith Creek. Hilton was the plantation of Revolutionary War patriot leader Cornelius Harnett. He died in British-occupied Wilmington as a prisoner of the Crown in 1781. The house at Hilton was demolished in the late 1800s, but the place became city property. It has long been the site of a city water treatment plant. From 1928-2012, a huge live oak at Hilton was decorated with lights and celebrated as “The World’s Largest Living Christmas Tree”.

Another fragment shows the area near the mouth of the Cape Fear River. One can read bits of text such as “Oak” for Oak Island; “Elizabeth R” for the Elizabeth River; “… mans” for Dutchman’s Creek; and what seems to be “For…” for Fort Johnston (in modern-day Southport).

We have parts of at least two ceramic Cape Fear maps, because the words “Bacon’s Inlet” appear once in their entirety, and again split into two fragments. Long gone but appearing on old maps, Bacon’s Inlet was near Holden Beach.

Some fragments from the borders of the maps show measurements of latitude. The 34th Parallel North passes through Kure Beach, about two miles north of the Fort Fisher State Historic Site. A degree of latitude (equivalent to about 69 miles, or 60 nautical miles) is divided into 60 minutes (about 1.15 miles, or 1 nautical mile), each of which is divided into 60 seconds (about 101 feet).

The right and left edges of the Price-Strother and Potts maps, as well as a few of our map fragments, showed measurements of latitude. One fragment with the numeral 5 stands for the latitude 5 minutes north of the 34th Parallel North (this would run through Carolina Beach today). The upper right corner of the map was just north of the 34-degree, 15 minutes north mark. Fragments from the left side of the map showing Bacon’s Inlet bear the numbers “55”, standing for 33 degrees, 55 minutes north latitude.

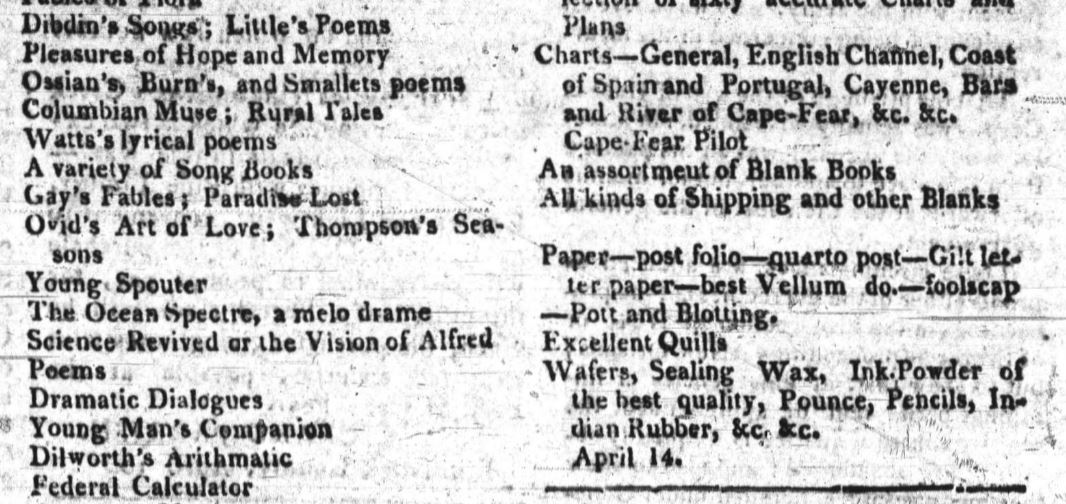

It’s quite possible our fragments came from black transferware pieces ordered by Joshua Potts himself. So far, no specific mentions of these unique Cape Fear souvenirs have come to light in surviving Wilmington newspapers from his time.

But, perhaps there are hints. In 1804-1805, Potts’ advertisements in the Wilmington Gazette mentioned crates of “Liverpool ware”. Liverpool ware was a genre of white-glazed ceramics such as creamware, which was decorated with transferware designs. Around the turn of the 19th century, Liverpool manufacturers exported many pieces designed for the American market. Perhaps Potts sent a copy of his map to Liverpool, with an order for some transferware souvenirs of Wilmington and the Lower Cape Fear region.

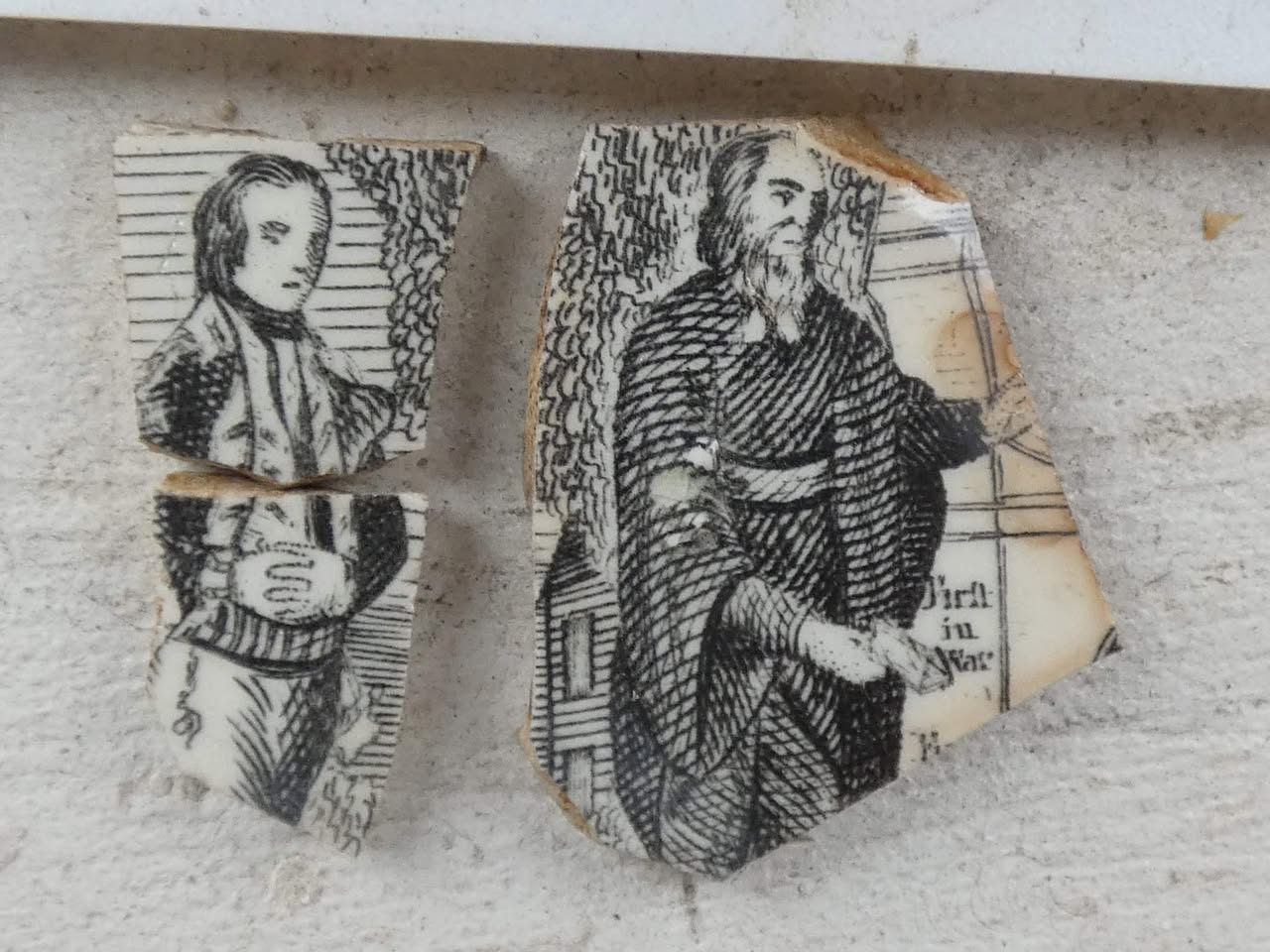

1

2

3

Our fragments came from a version of this early 19th century Liverpool ware pitcher. (The Magazine Antiques, Vol. XII, 1928, page 33.)

4

A printed handkerchief, made in Edinburgh, Scotland, has a similar image to our transferware fragments. (The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. “Fi. 17. Cotton handkerchief, printed by Johnathan Maclie and Company, Glasgow, Scotland…”)

5

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. “Fig. 18 Needlework picture, American. Inscribed on the monument, Washington/First/in/War/First/in/Peace/First/in fame/First in/Virtue…”)

Black Transferware Fragments that Honored George Washington

With its delicate engraving and tantalizing bits of text, black transferware pieces are among some of our most compelling finds at the Public Archaeology Corps’ Quince Alley dig in downtown Wilmington, North Carolina. Among these finds are some bits of a creamware pitcher made in the early 1800s, to commemorate the death of George Washington in 1799.

In the last days that our lab was open, we cleaned three pieces of the George Washington pitcher that belonged together. Two fragments show a young soldier in a military uniform of the time, and a larger piece shows what appears to be a clergyman standing by a stone memorial. A bit of text reads, “First in war”. Our pieces showed enough of an image for us to know they are variations on a design that some collectors called “Washington’s Tomb” or “the Washington Monument”. In the early 1800s, it was a popular design on jugs and pitchers. There are also examples of printed handkerchiefs and hand-embroidered textiles with this motif.

The full image shows symbolic mourners gathered around a stone monument with an image of Washington. Inscribed on the monument are the phrases “Born 1732”; “Died 1799”; “First in War”; “First in Peace”; “First in Fame”; and “First in Virtue”. Carved into the stone is an American eagle with its beak clamped on a Liberty Pole, topped with a Liberty Cap. To the left of the monument are two mourners, a young army officer and a clergyman. At the foot of the monument is another military mourner, a sailor. To the right of the monument is a figure to represent “Fame”, and a stylized American Indian to symbolize the United States and its place in the New World.

Some versions surround the design with a sort of chain with 15 links, each representing a U.S. state. This is actually a mistake, as the list includes the 13 original states, and the new states of Vermont and Kentucky. Tennessee was omitted, although it was admitted to the Union in 1796, three years before Washington’s death. Some of the versions also spelled two of the states wrong: “Kentuckey” and “Pensylvania”.

It’s likely these ceramic pieces were based on a print, although the original image is elusive. There were several versions of the image, and ceramic factories paired them with different designs on the back. Perhaps the oddest is a version with the Washington mourning image on one side, and artwork honoring British naval hero Admiral Horatio Nelson on the other. One example is in the collection of the Smithsonian’s American History Museum: https://www.si.edu/object/pitcher-admiral-lord-nelson:nmah_572398

Our Washington fragments were once part of a piece, probably a pitcher, of the type known to collectors as “Liverpool ware”. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, potters in Liverpool made a specialty of producing black transferware creamware, including many pieces with patriotic motifs for the American market. Liverpool ware is a useful term of classification, although not all black transfer creamware came from Liverpool. About 20 potteries were in operation in Liverpool in the 1700s and early 1800s, and they also made delftware, porcelain, stoneware, and other kinds of ceramics.

Perhaps some of our unidentified black transferware fragments will turn out to be part of the Washington pitcher. This will be one of many interesting projects for analysis once we get our lab up and running in a new home. Hopefully, that won’t be too long!

1

2

3